Brexit: All you need to know about the UK leaving the EU

What does Brexit mean?

It is a word that is used as a shorthand way of saying the UK leaving the EU – merging the words Britain and exit to get Brexit, in the same way as a possible Greek exit from the euro was dubbed Grexit in the past. Further reading: The rise of the word Brexit

Why is Britain leaving the European Union?

A referendum – a vote in which everyone (or nearly everyone) of voting age can take part – was held on Thursday 23 June, 2016, to decide whether the UK should leave or remain in the European Union. Leave won by 51.9% to 48.1%. The referendum turnout was 71.8%, with more than 30 million people voting.

What was the breakdown across the UK?

England voted for Brexit, by 53.4% to 46.6%. Wales also voted for Brexit, with Leave getting 52.5% of the vote and Remain 47.5%. Scotland and Northern Ireland both backed staying in the EU. Scotland backed Remain by 62% to 38%, while 55.8% in Northern Ireland voted Remain and 44.2% Leave. See the results in more detail.

What is the European Union?

The European Union – often known as the EU – is an economic and political partnership involving 28 European countries (click here if you want to see the full list). It began after World War Two to foster economic co-operation, with the idea that countries which trade together were more likely to avoid going to war with each other.

It has since grown to become a “single market” allowing goods and people to move around, basically as if the member states were one country. It has its own currency, the euro, which is used by 19 of the member countries, its own parliament and it now sets rules in a wide range of areas – including on the environment, transport, consumer rights and even things such as mobile phone charges. Click here for a beginners’ guide to how the EU works.

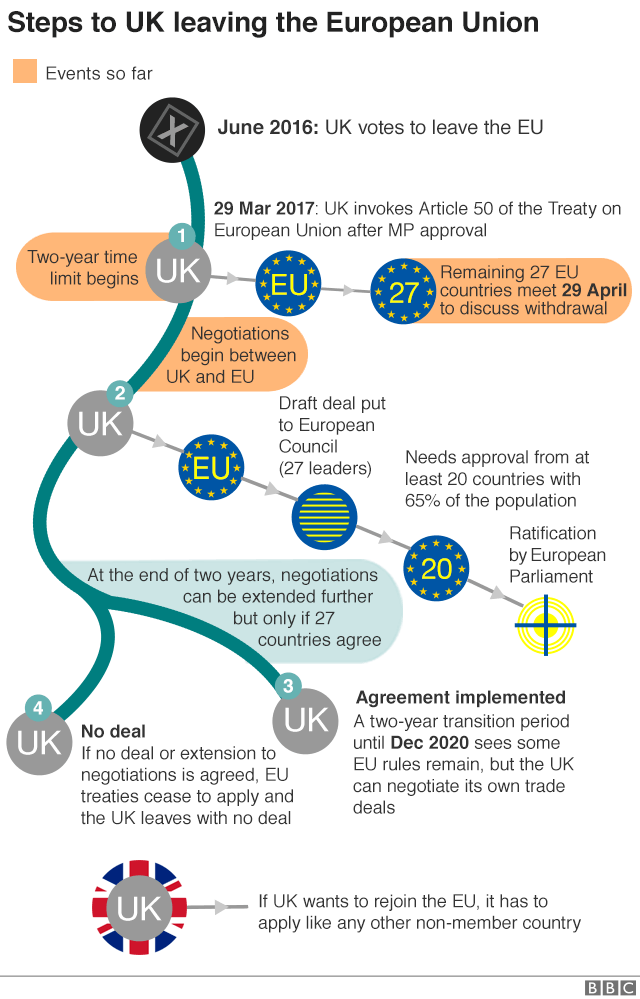

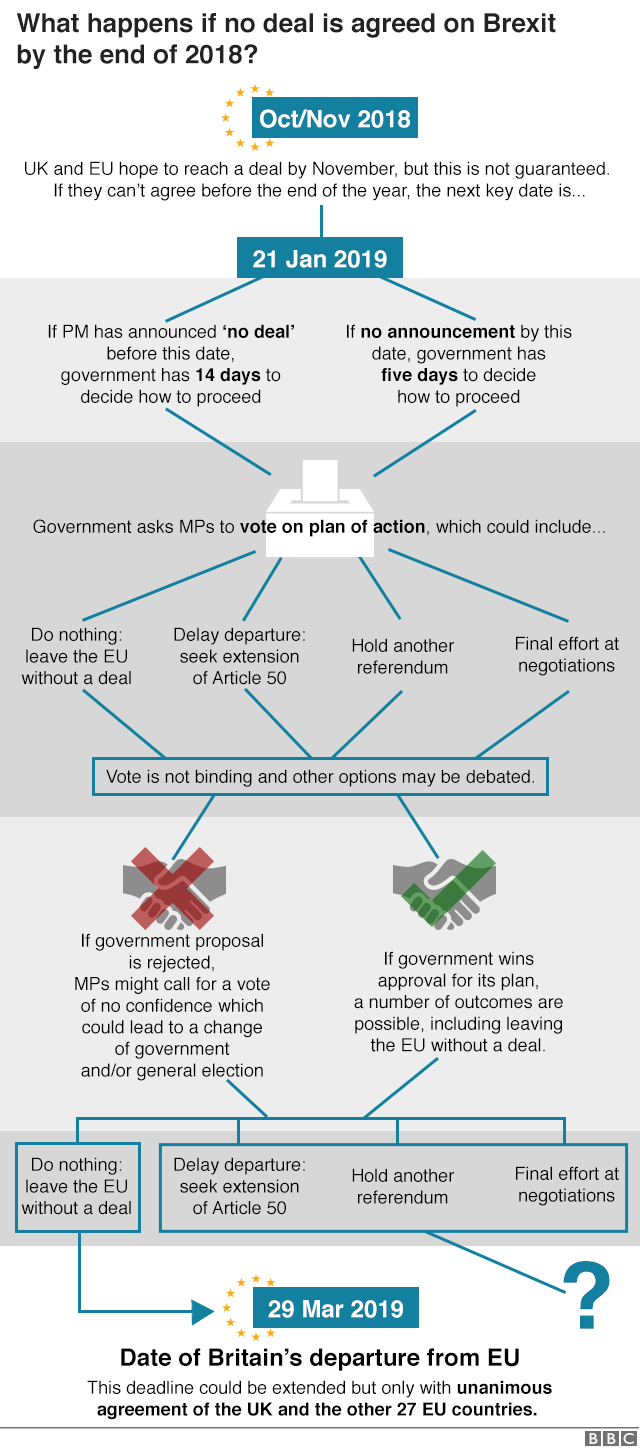

When is the UK due to leave the EU?

For the UK to leave the EU it had to invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty which gives the two sides two years to agree the terms of the split. Theresa May triggered this process on 29 March, 2017, meaning the UK is scheduled to leave at 11pm UK time on Friday, 29 March 2019. It can be extended if all 28 EU members agree, but at the moment all sides are focusing on that date as being the key one, and Theresa May has now put it into British law.

So is Brexit definitely happening?

The UK government and the main UK opposition party both say Brexit will happen. There are some groups campaigning for Brexit to be halted, but the focus among the UK’s elected politicians has been on what relationship the UK has with the EU after Brexit, rather than whether Brexit will happen at all. Nothing is ever certain, but as things stand Britain is leaving the European Union. There is more detail on the possible hurdles further down this guide…

What’s happening now?

After months of negotiation, the UK and EU have come up with a draft withdrawal agreement. This covers how much money the UK owes the EU – an estimated £39bn – what happens to the Northern Ireland border and what happens to UK citizens living elsewhere in the EU and EU citizens living in the UK. It also proposes a method of avoiding the return of a physical Northern Ireland border. A separate and much shorter draft statement on future relations has also been agreed. To buy more time, the two sides have agreed on a 21-month “transition” period to smooth the way to post-Brexit relations. The UK cabinet will discuss the text on Wednesday. If they give the go ahead there should be an EU summit at the end of November to agree to it. It would then be up to the UK parliament and EU member states to each ratify the agreement, before Brexit day next March.

What is the ‘transition’ period?

It refers to a period of time after 29 March, 2019, to 31 December, 2020, to get everything in place and allow businesses and others to prepare for the moment when the new post-Brexit rules between the UK and the EU begin. It also allows more time for the details of the new relationship to be fully hammered out. Free movement will continue during the transition period, as the EU wanted. The UK will be able to strike its own trade deals – although they won’t be able to come into force until 1 January 2021. This transition period is currently only due to happen if the UK and the EU agree a Brexit deal.

- Further reading: UK and EU agree transition deal terms

- In a lot of depth: The 129-page draft withdrawal agreement

Do we know how things will work in the long-term?

No. Both sides hope they can agree by the end of November an outline of how things like trade, travel and security will work. If all goes to plan this deal could then be given the go-ahead by both sides in time for 29 March 2019.

- Theresa May’s speech setting out longterm plan

- May secures cabinet backing for Brexit plan

- EU adopts guidelines for next Brexit phase

What is the Chequers Plan?

Theresa May’s cabinet had a wide variety of views on Brexit – from those who opposed Brexit, to those who led the Leave campaign during the referendum. Getting them all to agree on a vision for the future has been quite a challenge. To do so, Mrs May invited her cabinet ministers to Chequers, her official country house in Buckinghamshire, in July to thrash out their differences and agree a plan.

The plan includes proposals for the UK to mirror EU rules on goods, plus the UK and EU being treated as a “combined customs territory” which would mean the UK would apply domestic tariffs and trade policies for goods intended for the UK, but charge EU tariffs and their equivalents for goods which will end up heading into the EU. The idea is that this would avoid the need for a visible border with the Republic of Ireland.

The plan suggests that the UK would also be free to strike its own trade deals with countries around the world, something it is currently unable to do as a member of the EU customs union.

Mrs May says the plan will also end the free movement of people “giving the UK back control over how many people enter the country”. But a “mobility framework” will be set up to allow UK and EU citizens to travel to each other’s territories, and apply for study and work.

A “joint institutional framework” will be established to interpret UK-EU agreements. This would be done in the UK by UK courts, and in the EU by EU courts. But, decisions by UK courts would involve “due regard paid to EU case law in areas where the UK continued to apply a common rulebook”.

Cases will still be referred to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) as the interpreter of EU rules, but “cannot resolve disputes between the two”.

At-a-glance: The new UK Brexit plan

What has been the reaction to the Chequers Plan?

The initial reaction was not positive – Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson and Brexit Secretary David Davis both resigned a couple of days after the plan was agreed at Chequers. And it has not gained much support since then. Both those who oppose Brexit and those who want a clean break with the EU are unhappy with what is seen as a compromise deal. The European Union has also said the trade parts of the proposals are unacceptable. Mrs May has so far stuck by the plan, saying it is a workable one which takes on board both the UK and EU’s red lines, is the best possible one for the UK and EU economies and avoids the need for a visible border on the island of Ireland.

Read more: Laura Kuenssberg on the fallout from EU rejection of Chequers Plan

The Brexit timeline

What if the UK and the EU do not agree a Brexit deal?

European Council President Donald Tusk’s rejected the Chequers plan at an EU summit in Salzburg, Austria, in September, leading to increased speculation that the UK could leave the EU without a deal. Mrs May has always insisted that “no deal is better than a bad deal” – but, like the EU, she says a deal would be the best option for everyone. The government has started planning for a no-deal scenario, while stressing it is unlikely. It has published a series of guides for industry, covering everything from pet passports to the impact on consumer protection laws and electricity supplies in Northern Ireland. The M26 in Kent has been closed overnight to prepare for possible queues of lorries at Dover. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn says it will be a “national disaster” if the UK leaves without a deal, but some Conservative MPs are arguing for a “clean break” with the EU. They say warnings of chaos in the event of a no-deal Brexit are scaremongering.

- Reality Check: The case for a ‘clean-break’ Brexit

- Brexit papers: What no deal could mean

- Pet travel warning in no-deal Brexit plan

- Eurostar disruption risk in no-deal Brexit

- No-deal Brexit planning shuts M26 overnight

Why is Northern Ireland such a sticking point?

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESThe UK’s 310 mile land border with the EU – between Northern Ireland and EU member the Republic of Ireland – might not have been everyone’s big issue during the 2016 referendum campaign, yet it has come to dominate Brexit talks.

Neither side wants to see a return to checkpoints, towers, customs posts or surveillance cameras at the border, in case it reignites the Troubles and disrupts the free cross-border flow of trade and people. But they can’t agree on a way to do that.

The EU’s solution was to set up a “common regulatory area” after Brexit on the island of Ireland – in effect keeping Northern Ireland in an EU customs union – if no other solution is found during trade talks. Theresa May says this would threaten to split Northern Ireland off from the rest of the UK – something she, and the Democratic Unionist Party, would never accept.

She says her Chequers plan would solve the problem by establishing a “common rulebook” for food and manufactured goods flowing between the EU and UK, with no need for regulatory checks at the border. Customs declarations and VAT checks could be done electronically, so there would be no need for a physical border. The EU does not like her Chequers plan, however.

The UK has also proposed its own temporary “backstop” arrangement if a new customs system is not ready in time by the end of the transition period. The backstop proposal in the draft EU withdrawal agreement is believed to avoid a return to a “hard border” by keeping the UK as a whole aligned with the EU customs union for a limited time.

Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU in the 2016 referendum, by 56% to 44%.

What is the backstop?

The key thing to remember about the Northern Ireland “backstop” is that it is a last resort – if all goes as planned it will never be used. The two sides want to protect an open border on the island of Ireland in the event that the UK leaves the EU without having agreed a solution as part of trade negotiations.

They do not agree on what this safety net should look like, however. The EU has suggested Northern Ireland stays aligned with its trade rules so new border checks are not needed. But Theresa May has said this would undermine the integrity of the UK, by creating a new border in the Irish Sea.

She has suggested the UK as a whole could remain aligned with the EU customs union for a limited time after 2020, when the planned transition period ends. This is the solution in the draft EU withdrawal agreement.

Some Tory Brexiteers say the backstop is not necessary at all because technological solutions can avoid a hard border.

What changed in government after the referendum?

Image copyrightPA

Image copyrightPABritain got a new Prime Minister – Theresa May. The former home secretary took over from David Cameron, who announced he was resigning on the day he lost the referendum. She became PM without facing a full Conservative leadership contest after her key rivals from what had been the Leave side pulled out.

Where does Theresa May stand on Brexit?

Theresa May was against Brexit during the referendum campaign but is now in favour of it because she says it is what the British people want. Her key message has been that “Brexit means Brexit” and she triggered the two year process of leaving the EU on 29 March, 2017. She set out her negotiating goals in a letter to the EU council president Donald Tusk. She outlined her plans for a transition period after Brexit in a big speech in Florence, Italy. She then set out her thinking on the kind of trading relationship the UK wants with the EU, in a speech in March 2018.