COVID-19 and Diversity: The Emerging Picture in California

David E. Hayes-Bautista, Ph.D. & Paul Hsu, M.P.H., Ph.D.

The coronavirus does not discriminate. Like the falling rain, it descends upon everyone, young or old, rich or poor. But there are patterns in who remains dry and who gets drenched during this pandemic.

“In early April, coronavirus infection in Los Angeles County appeared to be centered in wealthy areas, such as Beverly Crest, Bel Air, and Brentwood,” said David E. Hayes-Bautista, Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Director of the Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture at UCLA. Residents of these wealthier areas, he explained, enjoyed what he termed “protective social umbrellas” that mitigated the effects of the coronavirus, such as full health insurance, good access to health care, and the ability to get out of the coronavirus “rain” by sheltering at home until the storm passes.

“Since then, the infection has swept out of wealthy areas to less wealthy and poorer areas,” he added. He explained that residents of these low-income areas have far fewer protective social “umbrellas,” and those often have big holes in them, such as little or no health insurance, little or no access to medical care, and essential jobs that require them to stay “exposed to coronavirus—‘out in the rain,’ so to speak,” so that others can shelter at home: farmworkers growing and harvesting food, workers in meat-processing plants, truck drivers delivering necessities, and cashiers working within arm’s length of hundreds of customers each shift. In California, these essential jobs are often filled by Latinos and other minorities.

“Younger populations generally have lower overall mortality than older populations,” said Paul Hsu, a UCLA epidemiologist. He pointed out that the Latino population has a median age nearly fifteen years younger than non-Hispanic whites (NHW). “We can better compare COVID-19 mortality effects in different populations by using age-specific death rates,” that is, by comparing the deaths in similar age groups in California’s diverse population.

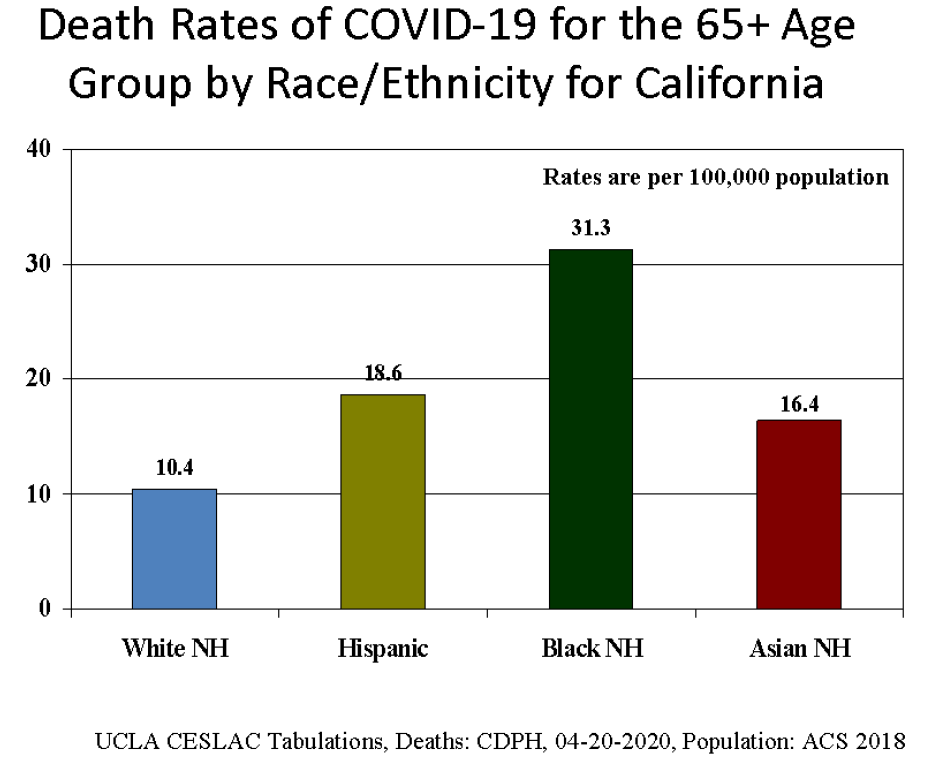

The age-specific mortalities for the four major racial/ethnic groups show how COVID-19 affects each group differently. Figure 1 (please see the report) shows that in the age group 65+ years old, the non-Hispanic white group has a mortality of 10.4 deaths per 100,000 NHW older adults. Latinos of similar age have a mortality rate of 18.6, and Asians a rate of 16.4, which are both close to twice as high as the NHW mortality. The African-American population has a death rate of 31.3, more than three times the NHW rate.

These death rates are very preliminary, but they strongly suggest how unevenly distributed protective benefits are among the state’s population. These rates are based on the first data released by the State of California stratified by age-group and race/ethnicity. As more data become available, we will update these figures. We expect that while the specific death rates will change somewhat in future reports, the overall pattern has already emerged and will not change much: the social “umbrellas” that most Latinos, African-Americans, and Asians rely upon in California have huge holes in them, and the result is higher age-specific death rates for these groups, compared to non-Hispanic whites.

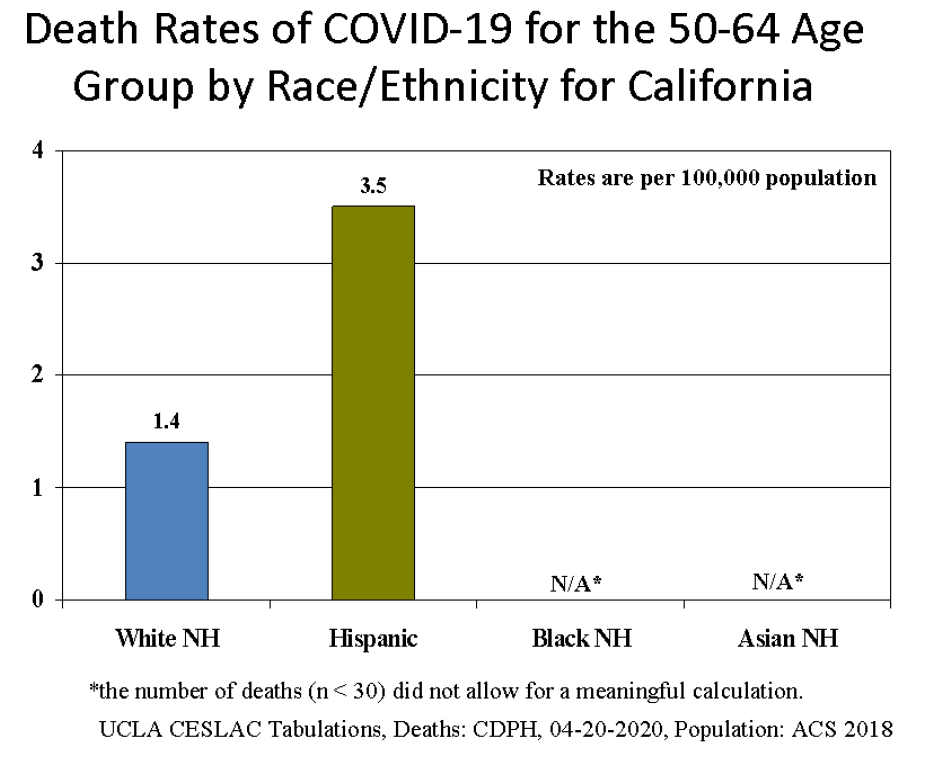

Figure 2 in the report shows death rates for ages 50‒64. Because the data released thus far record fewer than 30 Black and Asian deaths, respectively, in this age group, any rates calculated for these two groups would have been unstable and perhaps misleading. Therefore they have not been included in Figure 2 in the current report. As COVID-19 continues to ravage the state’s populations, these numbers are expected to rise; and we will include them in future reports.

Methods. The initial count of deaths from COVID-19 as of April 20, 2020, stratified by race/ethnicity and age group, was released by the California Department of Public Health (CDPH). Population denominators were tabulated from the 2018 American Community Survey, the latest available.

About CESLAC. Since 1992, the Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture (CESLAC) of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA has provided cutting-edge, fact-based research, education, and public information about Latinos, their health, their history, and their roles in California society and economy.

***David E. Hayes-Bautista, Ph.D., Distinguished Professor of Medicine, director of the Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture (CESLAC) of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA