Beijing injects new vitality into its Central Axis

By Fan Zhou, Sun Wei

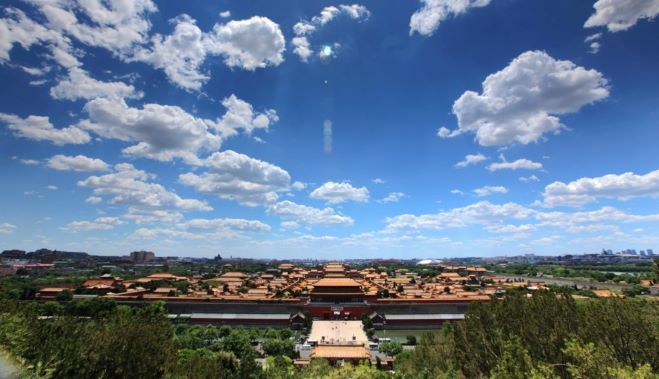

Photo taken on May 27 shows a view of the Palace Museum. Photo by Ding Bangxue/People’s Daily Online

Last April, Beijing issued the medium- and long-term plan (2019-2035) for promoting the construction of a national cultural center, specifying that the city will advance overall protection and revitalization of its old downtown area through efforts to make the heritage sites along its Central Axis inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Tourists enjoy themselves on the square of the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests in Tiantan Park in Beijing on Jan. 24. Photo by Zhang Jun/People’s Daily Online

Beijing’s Central Axis represents the essence of the city’s architecture and the cultural heritage and holds significance to promoting the construction of the national cultural center.

To bid for the World Heritage List and speed up the construction of a national cultural center, it’s both necessary and important for Beijing to comprehensively protect the Central Axis and carry forward the cultural heritage it stores.

Photo taken on May 27 shows a turret of the Palace Museum. Photo by Ding Bangxue/People’s Daily Online

Stretching for about 7.8 kilometers from Yongding Gate in the south of the city to the Bell Tower and Drum Tower in the north, the Central Axis is the most typical city central axis in China and also the longest and most complete existing central axis of a city in the world.

The Central Axis originated in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and took shape in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). With a long history of more than 750 years, it carries rich cultural connotations and has long served as the name card of Beijing’s culture.

In 2012, Beijing’s Central Axis was included on China’s Tentative List of World Heritage List, marking the beginning of a brand new chapter for protection of the Central Axis.

So far, 14 heritage sites along the Central Axis have been covered by Beijing’s bid for the UNESCO World Heritage List, including Yongding Gate, the Temple of Agriculture (Xiannongtan), the Temple of Heaven, Zhengyang Gate and its archery tower, Chairman Mao Memorial Hall, Monument to the People’s Heroes, Tiananmen Square, Tiananmen, Shejitan (the Altar of Earth and Harvests), the Imperial Ancestral Temple (Taimiao), the Forbidden City, Jingshan mountain, Wanning Bridge, and the Bell Tower and the Drum Tower.

All these sites, together with the historic roads and the buffer zones covering an area of about 51.4 square kilometers on both sides of the roads, will be prepared for a bid for the World Heritage List. These sites, roads, and zones account for around 65 percent of Beijing’s old downtown area.

In recent years, Beijing has spent great efforts on and seen significant results in vacating buildings and relocating residents of certain areas, as well as repairing cultural relics.

The efforts were followed by an endeavor to reuse these areas to bring new vitality and new cultural values to cultural relics.

Yangmeizhu Xiejie, a pilot site of Beijing’s exploration of new models for protection and renovation of historical and cultural blocks, adhered to the rule of authenticity instead of the old model of large-scale demolition and reconstruction in renovation, thus preserving as many as possible the historic features of the place.

The place has also introduced cultural and creative projects in the vacated areas of the neighborhood, saving nearly 70 percent original inhabitants from relocation.

Cultural heritages are not just relics of ancient times, they should also incorporates the characteristics and qualities of contemporary culture, which is why the efforts to protect the Central Axis of Beijing should involve a long-term mechanism to ensure a successful management of the surrounding areas besides vacating and renovating certain areas, so as to create a cultural atmosphere in which traditional architecture and landscape coexists with modern ones in harmony.

Cultural and historical sites in the city which have gained increasing popularity in recent years, including the Shijia Hutong Museum and the Dongsi Hutong Museum, are typical examples of preserving people’s memories of local culture.

Dashilan, a popular tourist area in Beijing, has made efforts to improve people’s living environment by designating public areas for ornamental flowers and plants and encouraging residents to grow flowers and vegetables in their own houses to strengthen exchanges, collaboration, and sharing of ideas among neighbors, intending to recover and restore the charm of Beijing’s unique hutong (a traditional narrow alley) culture.

In addition, Beijing’s Shichahai scenic area has also introduced the new business model of culture-themed homestay in recent years, which has spurred new ideas for vacating tasks, improved living conditions of local residents, and at the same time protected while reusing traditional spaces.

(Fan Zhou is the director of the School of Cultural Industries Management, Communication University of China. Sun Wei is a doctoral candidate of the school.)

(From People’s Daily Overseas Edition)