The Art of Penjing

Posted on October 28, 2020 by Usha Lee McFarling | Comments (2)

A penjing in the Verdant Microcosm, a new complex built to display a collection of the miniaturized plant landscapes in The Huntington’s Chinese Garden. Photo by Jamie Pham.

The venerable art of shaping trees and depicting landscapes in miniature—penjing—has existed in China for centuries. Now visitors to The Huntington’s Chinese Garden, Liu Fang Yuan 流芳園, can see more than two dozen examples of the art form, many created by one of The Huntington’s own experts. The penjing are on display in the Verdant Microcosm 翠玲瓏, a spacious courtyard within the newly expanded garden.

Penjing, considered living sculptures, have long been a part of classical Chinese gardens. Suzhou, the region of China that inspired Liu Fang Yuan, is particularly known for its school of penjing.

Handcrafted tiles illustrating the art of penjing grace the walls of the new display. Photo by Jamie Pham.

While the art form is little known in the United States, penjing has existed in China for roughly 2,000 years. Although the origins of penjing are uncertain, they were common in China long before the practice of bonsai took hold in Japan. Mural paintings in some Chinese tombs from the second and third centuries depict examples of penjing, notes Phillip E. Bloom, the June and Simon K.C. Li Curator of the Chinese Garden and Director of the Center for East Asian Garden Studies. “The art form is thought to have been introduced to Japan around the year 700, likely by monks, merchants, or diplomats,” Bloom says.

While related to bonsai, penjing are noticeably different. They are often more natural or “wild” looking, and they often depict landscapes rather than single trees. Penjing 盆景 is Chinese for a landscape or scene (jing) in a pot (pen). Whereas bonsai displays typically focus on a tree or trees, penjing displays can include elements other than trees, including rocks, water, or figurines. Penjing artists often say they are striving in their work to reveal the inner beauty, or essence, of nature.

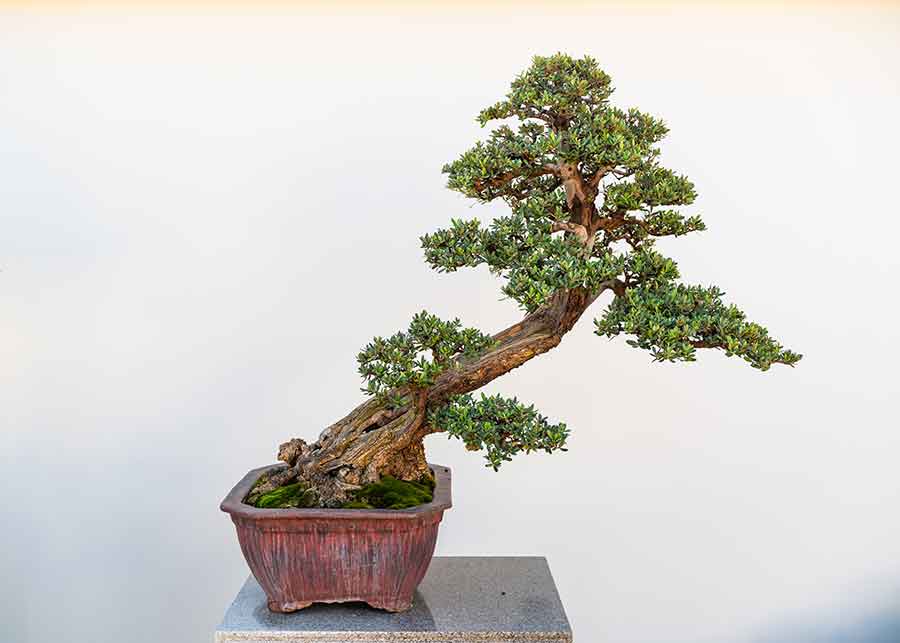

Penjing , like this one created from an olive tree, often capture the dramatic shapes trees can take in the wild. Photo by Jamie Pham.

The Huntington’s collection of about 60 penjing is due to the work and dedication of one man: Che Zhao Sheng.

Che, 69, has worked as a gardener at The Huntington since 2006. His main job is to tend to plants in the Chinese Garden and prune them. About a decade before he emigrated to the United States from China, Che developed an interest in penjing. He was able to study with penjing artist Lu Xue Ming, who was trained in the Lingnan school, one of several regional Chinese schools of penjing. “My teacher was considered a top master of penjing in China,” Che says.

Many of the works from this school are considered to spring from and even exceed nature. Sometimes using wire to train branches in a certain shape, the Lingnan school more frequently relies on a “clip and grow” technique: Branches are clipped as they grow to encourage dramatic twists and turns. The development of a single penjing can take decades; Che has worked on some of the trees now on display at The Huntington for more than 30 years.

Che Zhao Sheng studied the art of penjing in his native China and has created many of the penjing now on display in The Huntington’s Chinese Garden. Photo by Jamie Pham.

When he moved to the United States in 1986, Che worked in various jobs but continued to develop his penjing skills by working on trees he kept in his backyard. He also volunteered at The Huntington. Since penjing was little known here, Che had to enter bonsai exhibitions in order to display his work. It was at one of these exhibitions that Che’s work caught the eye of Jim Folsom, the Marge and Sherm Telleen/Marion and Earle Jorgensen Director of the Botanical Gardens. Folsom hired Che to work in the Chinese Garden and begin detailed pruning of the garden’s many pines so that they would reflect a Chinese, rather than a Japanese, style of pruning. Che made a strong impression right away.

“He’d grab a branch, like in the rodeo when you’re steer wrestling, and I’d hear branches cracking. I said, ‘Are you sure you know what you’re doing?’” recalls David McLaren, curator of the Asian gardens. “I was cringing, seeing him do this to plants that cost thousands of dollars—I’d never seen anyone do that to a pine before, but he said, if you don’t do that cracking, it takes twice as long to train them.”

Che carefully tends to The Huntington’s penjing , many of which he spent decades creating. Photo by Jamie Pham.

Che, working in the Chinese style, was striving to make the pines look more natural—less like perfectly manicured triangles. “We try to make Chinese pines look like something you’d find while walking in the mountains,” he says. That natural look is something Che also strives for in his penjing. “The goal is to create the sense of a tree as though you took it out of nature,” says Che.

“He’s a genius,” Folsom says. “I’ve never seen someone who can take a beat-up old stem and turn it into a beautiful penjing like he can.”

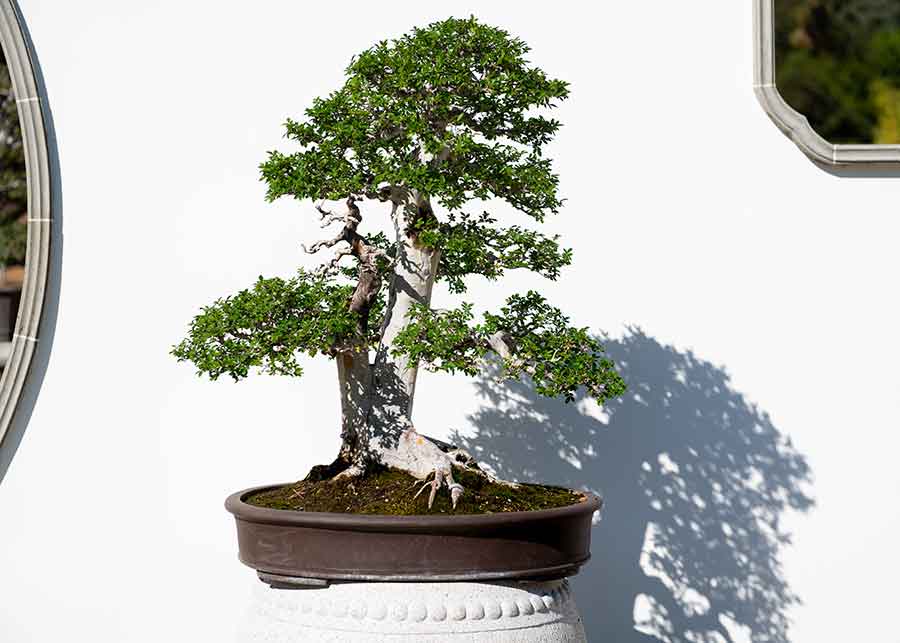

In the Cloudy Forest Court 雲林院, one of the architectural features within the Verdant Microcosm, Che’s penjing are displayed as they sometimes are in China, against white walls; the shadows they cast are considered an important part of the display. “Those shadows become like an ink painting that is moving on the wall,” Bloom says, adding that many consider penjing a form of three-dimensional painting. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, penjing were specifically designed to replicate painters’ compositional styles.

Penjing are often displayed against white walls so their shadows can add additional viewing complexity. Photo by Jamie Pham.

For many visitors, the penjing are more than just a beautiful display. They provide a deep connection to their homeland and memories of family. Mei-Lee Ney, who serves on The Huntington’s Board of Governors, was born in China, and she still treasures memories of the four elaborate penjing that stood on carved stone pedestals in the courtyard of her family’s mansion—Wu Dau Tai—built in Yichang for her great-grandfather, who had been the city’s governor.

“Those magical penjing were destroyed during the war with Japan and lived only in my mother’s memory, and thus in mine. They will always be important to me because they remind me of my mother and my own roots,” says Ney, a major donor to the Chinese Garden whose support made possible the construction of the Cloudy Forest Court for penjing display. “I had always thought of penjing as a fantasy lost in the past. You can imagine how thrilled I was that the penjing garden was part of the Chinese Garden’s expansion plans.”

The Cloudy Forest Court 雲林院, one of the architectural features within the Verdant Microcosm 翠玲瓏, the Chinese Garden’s new penjing complex. Penjing are displayed amid distinctive scholar’s rocks, making for dramatic viewing. Photo by Jamie Pham.

The new penjing display will allow many Huntington visitors to appreciate the differences between bonsai and penjing, says Ted Matson, curator of the bonsai collections. “Bonsai are more subtle, internal, and contemplative,” Matson says. “Penjing can be more extreme. They can replicate exaggerated things you might see in nature—like corkscrew twists, weird angles, and folds in branches—that can be pretty magical.”

Matson says the current display focuses on the Lingnan school because of Che’s training but that he hopes to add penjing from other schools to The Huntington and bring in the masters of those schools to demonstrate their techniques.

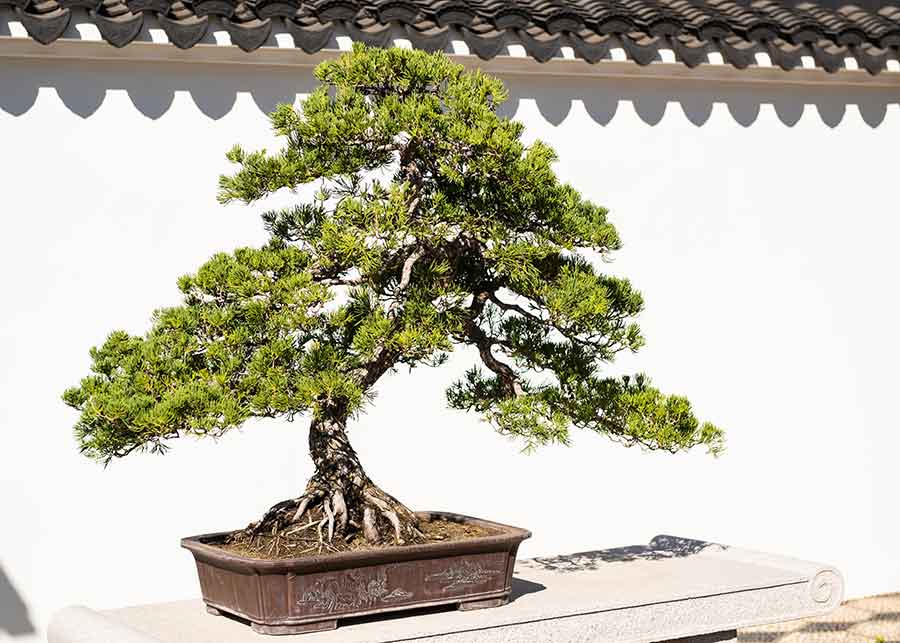

This penjing , created from a Juniper tree, includes graceful curves and turns of branches resulting from years of tending. Photo by Jamie Pham.

Other countries, such as Vietnam and Korea, have their own versions of the art form. “Many East Asian cultural traditions have their own take on miniaturized plants. It’s interesting to look at the stylistic differences,” says Bloom, noting that “many of these traditions have become amalgamated in the United States.” And even though bonsai originated from penjing, bonsai is likely to have influenced modern penjing once the tradition reemerged in China after the Cultural Revolution, notes Michelle Bailey, the curatorial assistant in the Center for East Asian Garden Studies.

Fortunately for visitors to The Huntington, the penjing tradition here is strong.

“This has been part of my grand plan all along,” Che says with a smile. “When I was learning in China, my teacher told me if I could show penjing to people in the United States, he would be very proud. We want people to know that, just as Japan has a tradition of bonsai, China has a tradition of penjing.”

Usha Lee McFarling is senior writer and editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington