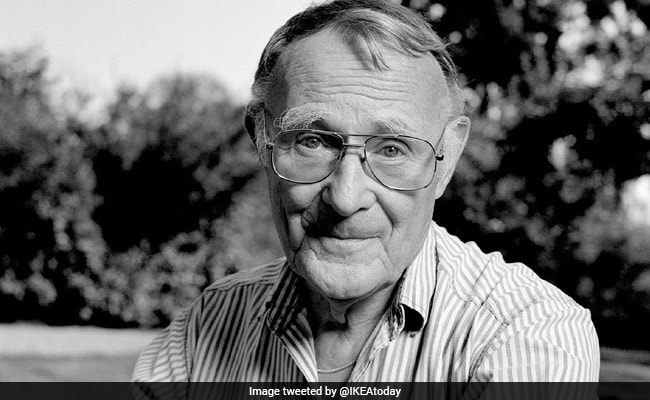

Ikea Founder Ingvar Kamprad Dies at 91 in Sweden

One of the great entrepreneurs of the 20th century, Ingvar Kamprad, the founder of IKEA, passed away today. Kamprad created a store — as a teenager mind you — that today has more than 400 locations, revenues of $62 billion, and a cultural ubiquity that very few consumer products could ever hope to attain.

Having read the IKEA story over the years and in various forms, there are just so many lessons to take from the one-time startup turned corporate behemoth.

The biggest innovation that Kamprad discovered was that consumer inconvenience could be massively lucrative. As Youngme Moon, a business professor at Harvard Business School, wrote in her book Different : “Most global brands build their reputations around a set of positives—the good things they do for their customers. What’s intriguing about IKEA is that it has consciously built its reputation around a set of negatives—the service elements it has deliberately chosen to withhold from its customers.”

IKEA is quite literally the antithesis of the view that the consumer is always right.

Kamprad realized that furniture could be “flat-packed” to massively reduce the cost of shipping and transportation, which at the time were among the product’s largest cost drivers. Table legs are unwieldy, so why not just take them off?

Except, now every consumer buying furniture would have to assemble it. In the case of complicated furniture items like armoires, there can easily be fifty or more steps involved in the construction of the piece, with an instruction guide that remains as confusing as ever at all the key steps.

Yet consumers love it, so much so that researchers have actually studied the effect of consumers investing their own labor into a product as The Ikea Effect. What researchers have found is that consumers love products far more when they complete the assembly themselves, because the labor we invest makes it seem as though the product is ours. Irrational, yes, but that predictable love ensured that consumers repeatedly flocked to IKEA stores.

Indeed, that investment of labor is so key to the brand that IKEA has famously resisted building out a delivery and installation crew à la Geek Squad to continue to force customers to build their furniture (or at least switch to TaskRabbit).

Flat-packing was hardly the only inconvenience that IKEA created though. It purposely built big-box warehouses to sell its products on the outskirts of cities near major ports or transportation hubs — improving logistics while cutting costs due to cheaper rents and larger scale.

Kamprad and his team knew that with the right price and product mix, consumers would drive to IKEA as a destination shopping experience — they had to bring their cars anyway of course to bring their purchases home. The team also understood that unlike a grocery store, furniture shopping is not a daily or weekly occurrence, and so people tended to invest significant time at the store when they finally did make the trip. That’s one of the reasons that IKEA has restaurants serving those scrumptious Swedish meatballs. The more time consumers spent in the store, the more they spent with their wallets.

And when they did open their wallets, they were able to buy more and more furniture over the years as the company grew in scale. IKEA’s product lines rarely shift, and so the company can fine-tune the production of each product to minimize cost. As FiveThirtyEight analyzed, the Poäng chair’s price has decreased from $300 at its launch in the late 1980s to just $79 today, inflation adjusted.

Finally, and not to be underestimated, Kamprad understood that furniture didn’t have to be like a family heirloom passed down from generation to generation. He might have just gotten the timing right, but the latter half of the 20th century saw some of the first evidence that workers would actively move between cities to seek the best employment. IKEA wasn’t furniture you shipped across the country, it was furniture you dumped and bought new again. Environmentally devastating perhaps, but efficient and convenient for newly mobile young people.

There is more to the story of IKEA of course, and Kamprad has received his fair share of criticism around early youth activities as a member of a far-right nationalist group and his resistance to paying taxes.

What’s a shame though is how many founders have never learned the stories and the lessons of the company and its success. Kamprad is hardly a household name, anymore than James Sinegal (founder of Costco) or John Mackey (founder of Whole Foods, who might be a bit more familiar to Austin-based entrepreneurs). At times in the tech startup world, we can be so narrow in our definition of a startup and of entrepreneurship, that these sorts of founders who have done things in other industries or just in very different ways don’t even register on our scopes.

Yes, Larry and Sergey, Steve, and Elon are all important in the annals of our industry. But ultimately we are in the debt of hundreds of of founders who have been brilliant in their own ways. In Ingvar Kamprad’s passing, let’s try to expand our vernacular to encompass more startups, and celebrate the kind of original thinking that has completely reshaped our world.