In 2014, Prem Pariyar’s father, who lives in Kathmandu, rented a truck for a day at a cost of 50 Nepali rupees. He asked the owner of the truck to come back the following day to get the payment, the equivalent of 38 cents in the U.S.

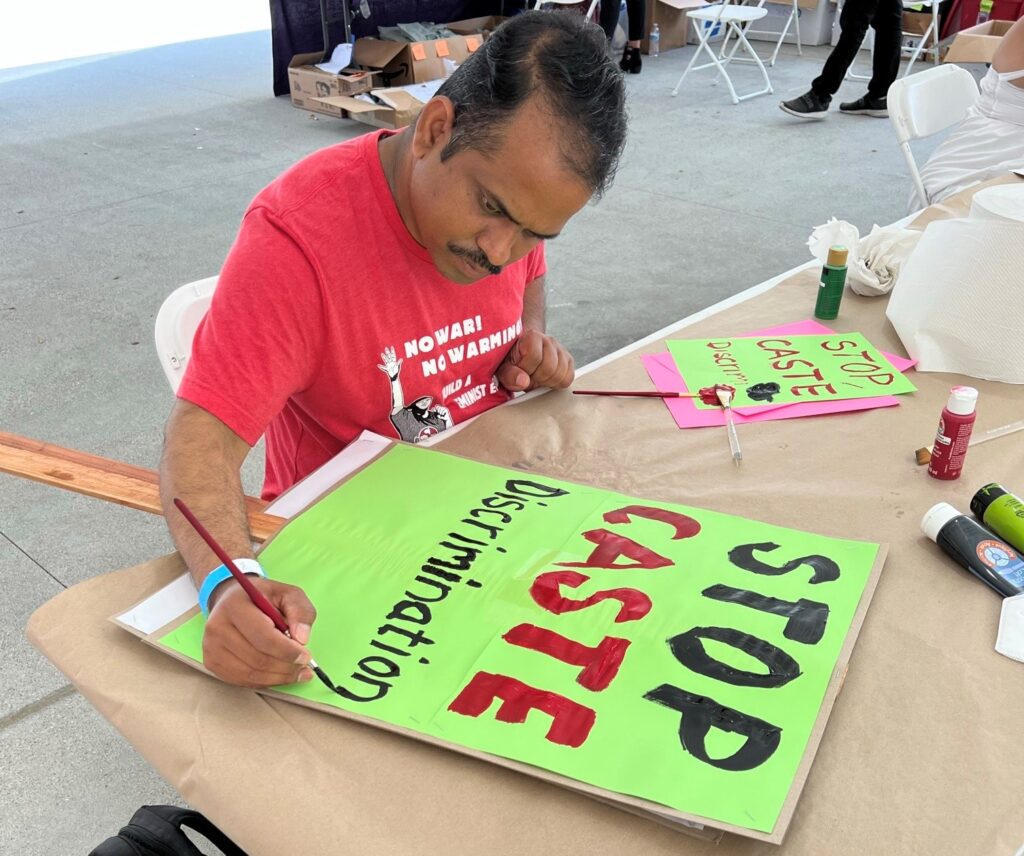

Pariyar’s family are Dalits, sometimes derisively referred to as “untouchables.” Caste oppression and discrimination are currently on the front burner in California: on May 11, the state Senate overwhelmingly passed SB 403, which would make discrimination on the basis of caste illegal in the state. The bill was sponsored by Democrat Sen. Aisha Wahab, the first South Asian American woman in the California state Legislature.

Brutal Attack

If the bill passes through the Assembly and is signed by Governor Gavin Newsom, California would become the first state to explicitly ban caste-based discrimination. Opponents of the measure say protection for Dalits already exists in California state law.

The Seattle, Washington City Council passed a similar resolution in February.

Pariyar told Ethnic Media Services the truck driver was very angry. “He said: ‘oh, you untouchables. How you dare to say that? Do I have to come again just to receive Rs 50? Okay, wait, I will show you your label.’”

The truck owner came back with 25 men, who broke through the door of the Pariyars’ home and tore the place apart, according to Prem Pariyar. He was not home, but his mother, father, sister, wife, and little son were all inside.

Pariyar alleged that the higher caste truck owner and his gang started to attack his sister and father, viciously beating them while chanting anti-Dalit vitriol. “My dad fainted, he fell to the ground.”

Brain Bleed and Nightmares

Pariyar’s wife called Prem, who returned immediately and called police. The family was taken to the hospital. Pariyar’s father sustained a slow brain bleed, which lasted about six months. His mother and sister suffered extensive bruising throughout their bodies. The family remains traumatized to this day, often suffering nightmares of the horrific event, he said.

Pariyar said he tried to file a report with police, but allegedly got nowhere. He fled to the U.S. in 2015, using caste oppression as the basis for his asylum claim, which was approved by the State Department, according to him.

State Dept. Criticizes India and Nepal

At press time May 19, the State Department had not responded to a request for comment on Pariyar’s case or whether caste oppression is a valid criteria for asylum cases. But in its annual “Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – the Human Rights Report,” the agency noted that while caste-based discrimination is illegal in Nepal, the practice still continues and is often violent.

The report cited Dalit activists as saying discrimination laws were too general and did not explicitly protect Dalits. Most cases go unreported, and those that are reported rarely result in official action, according to the State Department report.

Asylum in the US

The State Department cited similar conditions in India. The Indian Ministry of External Affairs immediately denounced the report as “motivated and biased commentary” and added that “such reports continue to be based on misinformation and flawed understanding.”

Pariyar’s case is an acknowledgement that the State Department recognizes that caste oppression is a valid condition upon which to approve an asylum claim, said Thenmozhi Soundararajan, founder of the Oakland, California-based Equality Labs, the largest Dalit organization in the U.S. “Caste discrimination is a known reason for asylum; we have seen cases across multiple states,” she told EMS.

Discrimination Continues

“Immigration case law is one of the robust bodies of US law where caste discrimination is recognized,” said Soundararajan.

After fleeing to the US, Pariyar attended college at CSU East Bay; discrimination against him persisted by other South Asian Americans.

“People used to ask my name. When I said ‘I’m Prem Pariyar,’ their body language changed immediately. Silence descended. They could tell by my surname that I was Dalit.”

“So many people in my community have changed their surnames to hide their caste identity. But I have never hidden who I am,” said Pariyar.

‘Polluted’ Food

The associate mental health clinician, who is currently practicing at the Portia Bell Hume Behavioral Health and Training Center, said that shortly after arriving in the US, he went to a house party. “When it was time to have food together, I was stopped many times. They didn’t want me to touch the food because I would pollute it. They have a fear of polluting their food.”

A similar incident occurred at a contract worksite, during a birthday celebration of a Nepali co-worker. Everyone at the office was invited, so Pariyar went. But when he went to get his food, he was stopped. “The hostess immediately stopped me. ‘Excuse me, Prem, can you stop? Please don’t touch that food. I will prepare a plate for you.’”

“This happened in front of my fellow co-workers. I was feeling like I was not a human being at that time,” said Pariyar. “I was so embarrassed. But nobody stood up and told the hostess ‘this is wrong,’ which made me feel even more bad.”

‘Casteism Still Alive’

Spurred on by Pariyar’s activism, in January 2022, the California State University system added caste as a protected category to its system-wide anti-discrimination policies.

“I used to think the United States, this is the dream land for everyone. Because here people can have all kinds of freedom. This is the land of human rights.”

“But the truth is, casteism is still alive and well today in California. Dalits are suffering daily from the effects of historic and modern casteism,” said Pariyar.