In the hottest labor summer in 40 years, unions are demanding better contracts for working people who can’t live on their paychecks. And solidarity across all sectors is making a difference.

This is the view shared by veteran union organizers, labor economists, and striking workers alike during a recent EMS Zoom briefing.

“We did not have shelter, so we were homeless much of the time. We didn’t have access to healthcare,” said California State Senator Maria Elena Durazo, who is the daughter of migrant farmworkers. “And, of course, we lived in poverty for poverty wages for a very, very powerful, very wealthy industry,” Durazo said.

It wasn’t that the industry couldn’t afford it, she noted. “It was simply that the workers didn’t have the power of collective bargaining.”

Thirty years ago, Durazo organized Latino immigrant workers in California to change that dynamic. “The labor movement had a vision,” she said.

Today, that vision is under threat from an array of forces, including California’s sizable gig economy, which employs some 1.3 million gig workers, about half of them drivers for rideshare companies where they are classified as contractors and are therefore denied worker protections and benefits.

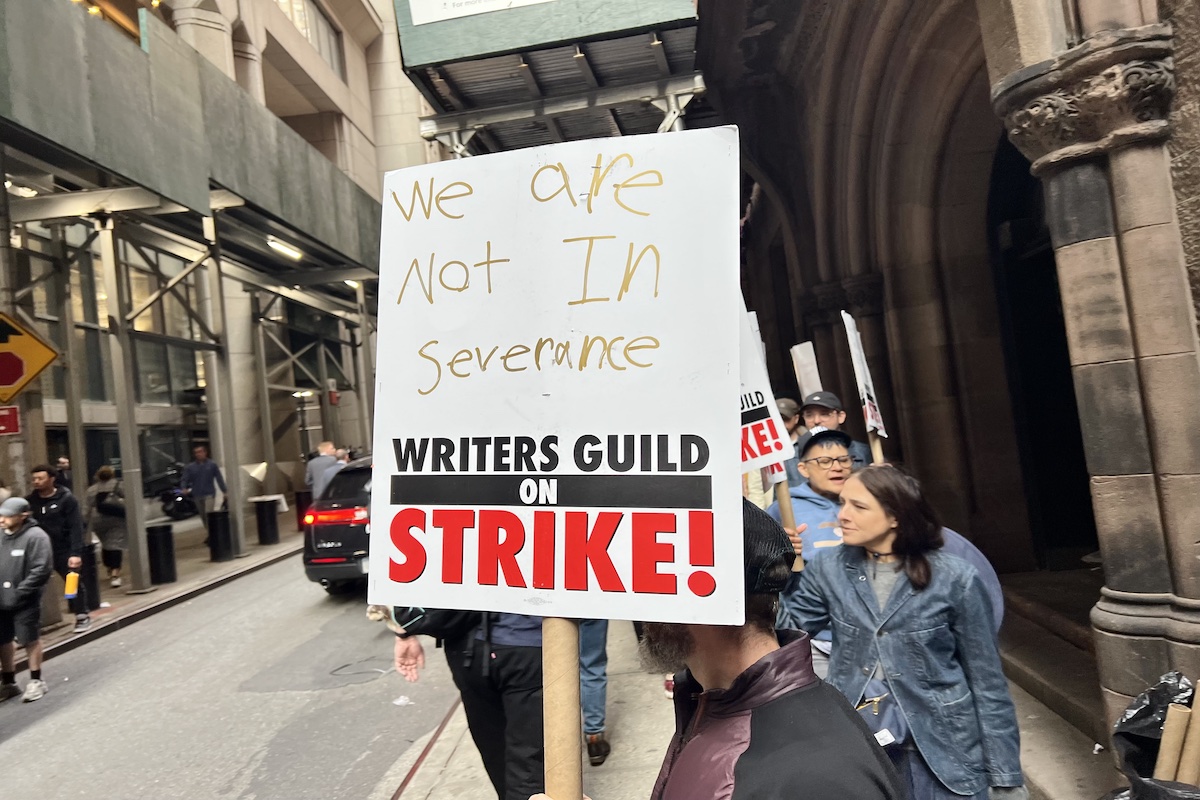

Workers are increasingly taking to the picket line in response. Actors and writers in Hollywood are for the first time in 60 years striking together. Some 15,000 hotel workers are staging rolling strikes at 43 hotels for a $5/hr. pay increase; UPS just signed an historic agreement that ends two-tier wages for part-timers; and auto workers at the Big Three could strike in September when their contract expires.

A new generation of labor leaders

According to labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein, today’s young firebrands are leading unions that are 80-90 years old. “At various moments in the past, they’ve kind of been rotten or corrupt or ineffectual,” he said.

Unlike in the 1930s when auto, steel, mining, and electrical unions had contracts with important industries, Lichtenstein noted that while just 6% of workers in the private sector are in unions today, that may be shifting.

A tight labor market with very low unemployment favors organized labor, he noted, adding that the pandemic delegitimized employers and other institutions that didn’t take care of people in the same way the Great Depression eroded faith in big business in the early 1930s.

He drew another parallel with the Civil Rights Era when people felt a sense of “justified and moral grievance against employers” who did not treat all workers equally.

These days it’s not uncommon to see famous athletes and movie stars publicly champion causes. Meanwhile minor league baseball players have formed a union. University teaching assistants have recently gone union also. College athletes could be next.

“It means something when these kinds of elite cultural figures side with the unions,” Lichtenstein said.

No homes for hotel workers

Ada Briceño is Co-President of UNITE-HERE Local 11, representing over 30,000 hotel workers in Los Angeles County, Orange County, and Arizona. “This is the largest strike in the hotel industry,” she said.

The hotel industry is making record profits while workers are struggling with inflation and the unbearable cost of housing. Hotel workers are couch surfing or sleeping in their cars or taking shifts in rented rooms in the afternoon if they work a morning shift, she explained.

“We have had strikes in Pasadena, in downtown LA, in Santa Monica, in Anaheim, in Irvine, and Dana Point, LAX, Beverly Hills, and many, many other cities. In case you haven’t had a chance to visit yet, our picket lines have been magnificent.”

So far, only one hotel has signed so the strikers and their supporters are maning the picket lines until they settle.

“Our demands are very simple. We want to keep hotel workers with a roof over their heads,” she said, adding, “wages, pension, healthcare, and workload issues are our top key issues.”

Briceño noted the strike has prompted cancellations by the Democratic Governors Association, Vice President Kamala Harris, Japanese American Citizens, W.K. Kellogg Foundation, and Snoop Dog. “We have tons of supporters,” she said.

Striking for a better life

Lucero Ramirez is a housekeeper at the Waldorf Astoria in L.A. “I want better pay to live a better life. I am worried about a pension and particularly after the pandemic that the workers secure healthcare for the future,” she said.

The Waldorf is a five-star hotel; the rooms are big, and require a lot of attention because the floors are marble and the rugs are imported from Italy. It’s hard work to clean six very large rooms a day.

She makes $3000/mo, pays $1,100 in rent and supports her elderly parents. Ramirez is afraid at some point she will have to move as the cost of living in LA continues to rise.

“I have many co-workers who drive 2 or 3 hours because they can’t afford to live here,” Ramirez said.

Jorge Rivera worked a number of non-union jobs producing true crime stories for Fox and the Discovery Channel before joining the Writers Guild of America (WGA). He now serves as the Vice-Chair of the WGA Latinx Writers Committee.

“I just want to convey a message of solidarity to my siblings in the hotel union. You all deserve exactly what you’re asking for,” Rivera told Ramirez during the press call.

There was a time when union and non-union jobs paid well in Hollywood. But the advent of streaming changed all that. Except for big name actors and directors, most of the 11,000 writers and actors in today’s Hollywood are gig workers barely making the $24,000/yr to get health benefits.

“So now writers are working 10 weeks out of the year if they’re lucky and actors are doing the same and the checks that are coming in are not really a sustainable income,” Rivera said.

Meeting the challenge of AI

Rivera noted the studios made about $200 billion last year and the guild workers are asking for 2% – about $450 million – “to keep everybody financially whole.” One big concern is that the studios plan to use AI tools in production.

“The studios are looking towards being able to use the technology to replace creatives. There’s been conversation about the ability for AI to replace directors, replace actors, replace writers, and quite frankly I feel like this is an existential fight that we’re on the forefront of, that will affect a great many other labor sectors after us.”

Last week the Mackenzie consulting firm came out with a new report indicating by 2030, 30% of all work hours will be impacted by artificial intelligence. So a huge number of workers will be facing in the future what the screen actors are facing today.

According to UC Berkeley Professor Emeritus Harley Shaiken, labor solidarity will be key to meeting this emerging threat.

“What we are experiencing right now this summer is a summer of solidarity.

And we’ve seen something that many Americans have forgotten – how vital solidarity is for gains that affect everyone,” he said.

“So the Teamster drivers will be making over $49 an hour at the end of this contract. That will stimulate economic growth. It also sets the standard for workers in other areas of the economy who are also going to benefit,” Shaiken said.

Feature image via Wikimedia Commons.