Slow-growing U.S. green card caps, delays and waste have characterized the system for a century, and are only worsening under politically polarized immigration laws.

At a Friday, March 1 Ethnic Media Services briefing, immigration policy experts discussed how we have reached our present crisis, economically sound solutions and the human cost of our current system.

A century of green card caps

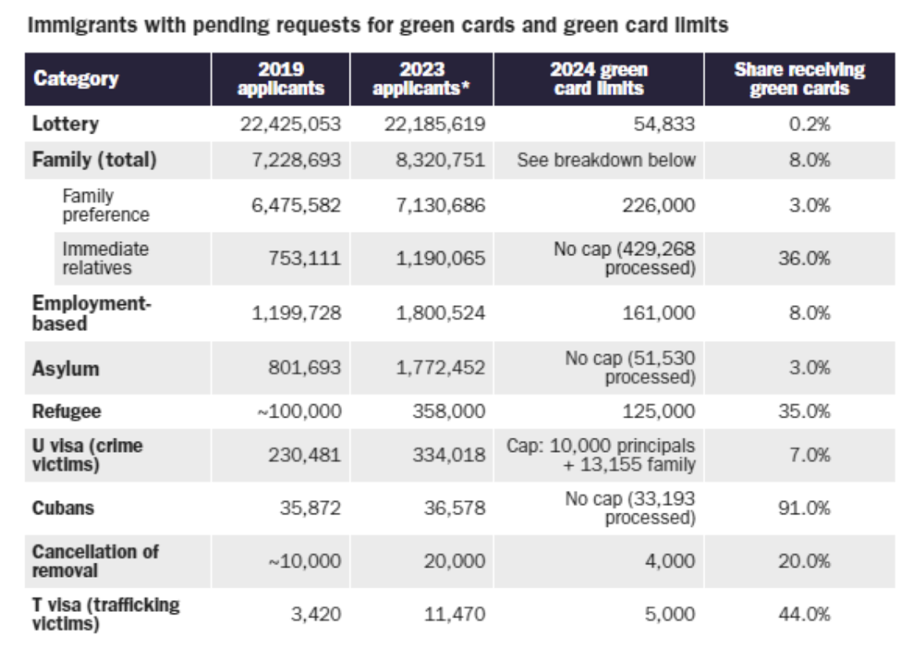

In 2024, 1.1 million people are expected to receive green cards from 35 million pending applications. In other terms, only about 3% of the people who have submitted green card applications will receive permanent status.

This low approval rate owes not to the convoluted process of applying for a green card but to green card caps, said David J. Bier, Associate Director of Immigration Studies at the Cato Institute. Until 1922, when backlogs began, about “98% of the applicants who tried to get the then-equivalent of legal permanent residence were approved.”

By the mid-1920s, the approval rate was about 50% due to the Immigration Act of 1924, setting “very low numerical limits based on country of birth, particularly restricting legal immigration from Eastern Europe and Asia. In the early ‘30s, we adopted a later phased-out public charge rule that banned almost all applicants,” explained Bier. Approvals remained below 20% during and after World War II, “and this is how we got from open borders to what we have now, which is almost closed borders — a 98% approval rate down to 3% for the last few years.”

Despite the fact that green card applications have more than tripled from about 10 million in 1996 to 35 million now, modern caps — which were originally set by the Immigration Act of 1990 — have barely risen, from 357,000 annually in 1922 to just over 575,000 in 2024.

“The caps are arbitrarily determined by the President in consultation with Congress, they have no basis in reality,” said Bier.

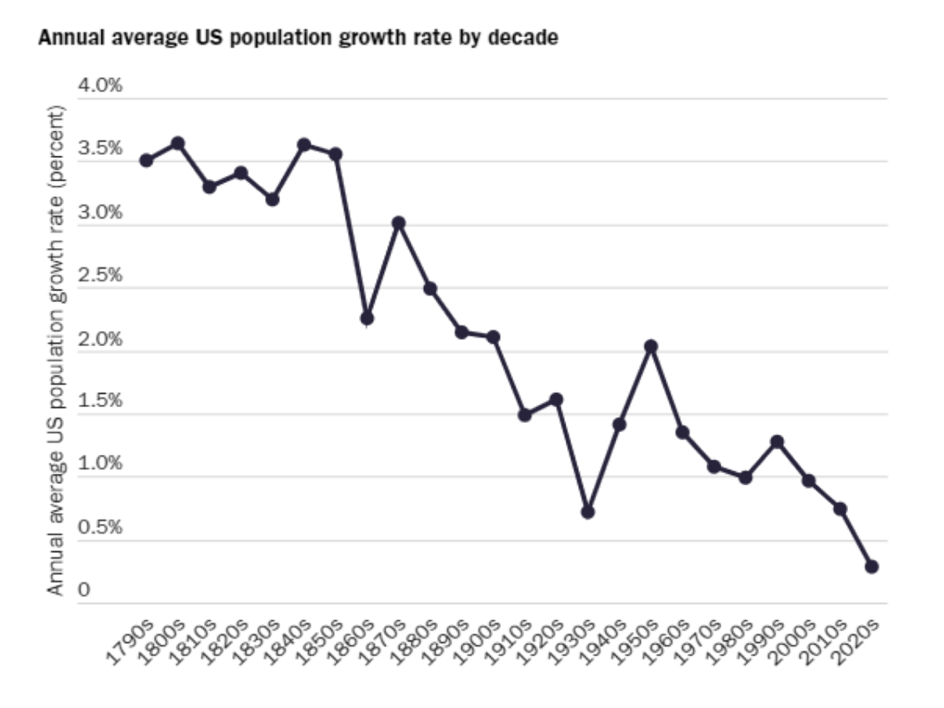

U.S. population growth — which was 0.1% in 2021 and has been roughly 0.25% this decade so far — has never been lower.

“Even if after accepting the 35 million pending green cards, we increased ongoing legal immigration five-fold, we still wouldn’t catch up to Canada’s foreign-born population share,” Bier added. “The U.S. is a huge country, there’s no reason population wise we can’t welcome these people.”

The economics

Clearing green card backlogs by welcoming more legal immigrants makes major economic sense, said Jack Malde, a senior immigration and workforce policy analyst at Bipartisan Policy Center.

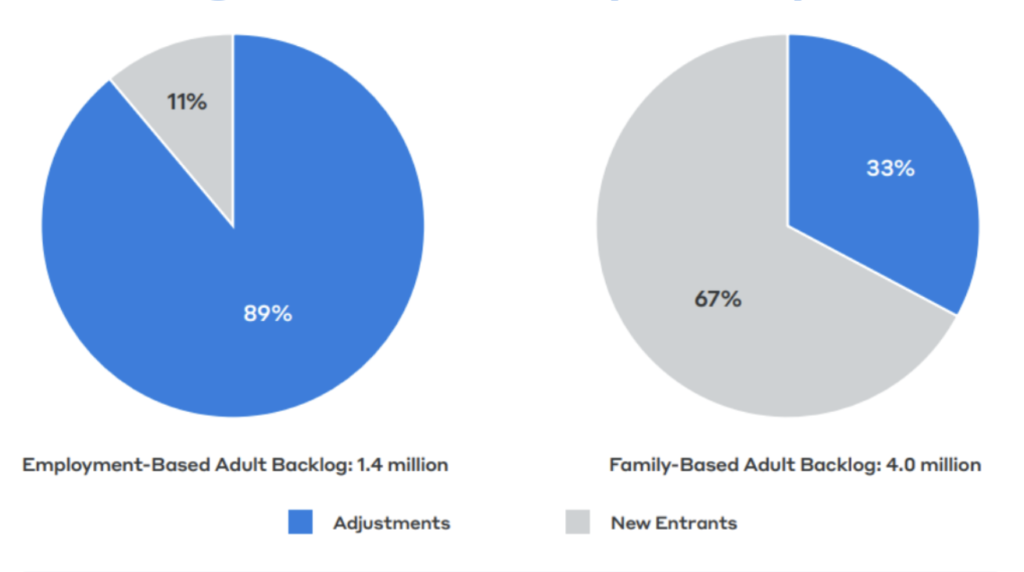

As 89% of the employment-based backlog involves people currently in the U.S. on temporary, work-restricted visas, “removing those labor market restrictions allows them to advance in their likely higher-skilled careers,” he explained.

“On the other hand, most of the family-based backlog are currently outside of the country, so green cards would allow them to contribute to our economy by paying taxes and entering our labor force, which is in dire need of new workers with shortages across industries and an aging population dependent on federal benefits,” Malde continued

As of March 2023 the employment-based adult backlog is 1.4 million (1.8 million total, across ages) and the family-based adult backlog is 4 million (5.8 million total), per a Bipartisan Policy Center report.

What would be the final gain?

Clearing current employment and family-based backlogs, not including future ones, would result in a moderate projection of $3.9 trillion in GDP gains in the next 10 years — though as low as $2.8 trillion or as high as $4.9 trillion.

U.S. immigrants who arrive at age 25 as high school dropouts have a net fiscal impact of +$216,000, not including descendants, which reduces their net fiscal impact to +$57,000. By comparison, American-born dropouts of the same age have a net fiscal impact of −$32,000 that drops to −$177,000 including their descendants.

“It’s a mistaken perception that there are a fixed number of jobs in the economy,” said Malde. “When immigrants enter the country, they create more jobs for U.S.-born workers, because they contribute their skills.”

The human cost

“Working legal immigrants and their children are in danger of falling out of status in a never-ending limbo,” said Cyrus Mehta, an immigration lawyer and founding and managing partner of Cyrus D. Mehta & Partners.

Employee-sponsored temporary visas like an H1 “get them in backlogs that last forever with extension after extension as non immigrants bound to employers, and in the process, the US loses,” he continued. “They get frustrated and go to countries with much more attractive immigration benefits and systems, like Canada, and so the US may not be able to maintain its world leadership with respect to attracting the best and brightest.”

Alongside spouses, the children of these sponsored immigrants get temporary H4 visas until 21, when they’ll most likely age out “due to horrendous backlogs,” Mehta explained. Even if the child gets a student F1 visa for college, “it requires them to have a non-immigrant intent to return to the foreign country.”

Meanwhile, there’s an H1 cap for employees with U.S. master’s degrees if the child continues to graduate school — and if the child is lucky enough to get one, they start the green card process again. The parent’s priority date cannot be transferred.

As a policy fix, Mehta suggested counting unified family units rather than discrete family members for caps in the employment and family-based categories, or allowing temporary visa holders already in the U.S. to file for early status adjustment before their priority date, so their children’s ages are frozen.

“But you can imagine what an unworkable, untenable, unhuman system this whole thing is, especially for a child who has been here for their whole life,” he said. “To free up visas, bipartisan agreement from Congress is hard, this issue is politically fraught … but once you show that an administrative policy is successful, then Congress may someday bless it. Parole is one example.”