Why most battery-makers struggle to make money

This is not your classic boom-and-bust cycle

The battery business needs a tune-upPhotograph: Getty Images

Boom-and-bust cycles all tend to look the same. A consumer fad or industrial urgency fuels demand for a product. Prices rise. Producers invest in capacity. By the time new supply materialises it outstrips already sated demand. Prices crash. Then, at some point, things get so cheap as to set off another demand upswing. And so on.

The inevitability is comforting for bosses in industries from mining to chipmaking. Not, though, in battery manufacturing. Anticipating booming demand for electric vehicles (EVs), since 2018 companies around the world have ploughed more than $520bn into battery-making, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a research firm. Sure enough, the investments (plus improvements in technology) have pushed down the prices of batteries and, since these make up a third of the cost of an EV, of battery-powered cars. But not sufficiently to entice motorists to go electric. And so the industry is facing a bust without ever having had much of a boom.

On July 7th SK On, a giant South Korean battery-maker building factories in America to supply Ford and Volkswagen, said it was in a state of “emergency management”. A few days earlier Northvolt, a European rival, announced a strategic review, potentially delaying new factories. LG Energy Solution, another South Korean firm, has paused work on part of a $5.5bn factory in Arizona. Its ratio of capital spending to sales rose from 10% in 2020 to almost 30% in the 12 months to March.

In contrast to more mature businesses with high upfront costs, such as semiconductor manufacturing or shipbuilding, long-term returns on investments in battery-making are hard to predict. The technology is evolving fast. More important, in the absence of historical demand trends, forecasts rely on consultants’ projections of EV uptake.

These appear to have been far too rosy, partly owing to overoptimistic assumptions about just how energetically governments would go about promoting electrification with carrots (such as subsidies for producers and buyers) and sticks (for example, carbon taxes and fuel-economy standards). In the absence of potent policies, carmakers are delaying their electric ambitions. Mercedes-Benz, which had hoped that half the cars it sells will be battery-powered or hybrid next year, has pushed that goal back to 2030.

Source:The Economist

Chart: The Economist

One way to solve this problem—and turn battery-making into a more normal industry—would be for companies to invest in inventing cheaper batteries rather than making pricier ones at greater scale. Another solution is freer trade. Prices in China, where most of the world’s EV batteries are manufactured nowadays, are down sharply. This helps explain why around one in two new cars sold to Chinese buyers is electric or hybrid, compared with less than one in five in America. In 2023 a benchmark cell manufactured by CATL, China’s battery champion, cost less than half what it did the year before.

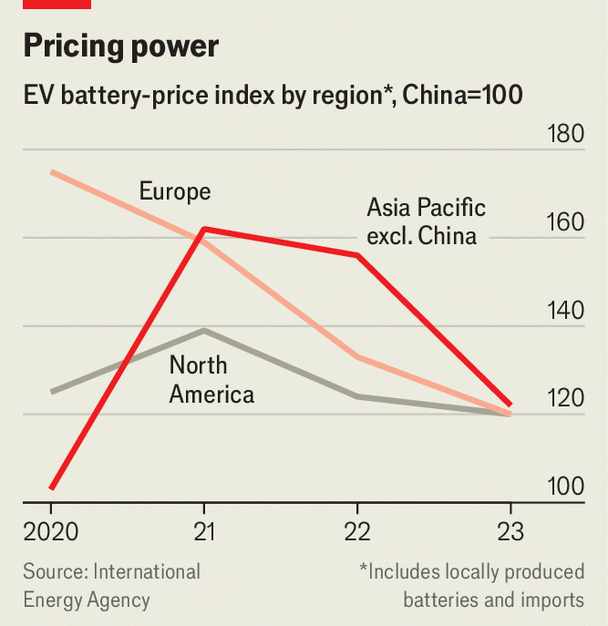

Yet these price drops have not spilled over to the rest of the world, where batteries still cost a lot more than in China, according to the International Energy Agency, an official forecaster (see chart). Many countries are putting up barriers to Chinese imports, often in the name of promoting domestic manufacturing. The result is that, outside China, battery-makers have not grown strong enough to stomach a bust—with no immediate boom in sight.

Source:The Economist