With California hate crimes nearly doubled since 2019, local leaders have sparked nationwide efforts to fight hate at the grassroots level amid low prosecution rates.

These efforts, part of an annual United Against Hate Week, began in mid-2017, after neo-Nazis sponsored a protest in Berkeley’s Martin Luther King Jr. Civic Center Park that involved bloody altercations between fascist and antifascist groups.

For this year’s proceedings in the week of September 21, events in over 200 communities nationwide include a Unity Walk in Las Vegas sponsored by the U.S. Attorney’s Office and Nevada’s Attorney General; a PBS-led screening and discussion of Repairing the World, a film about Pittsburgh’s response to the deadliest antisemitic attack in U.S. history, the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in 2018; a variety show against hate in Providence, Rhode Island; and resolutions to combat hate in cities throughout the Bay Area.

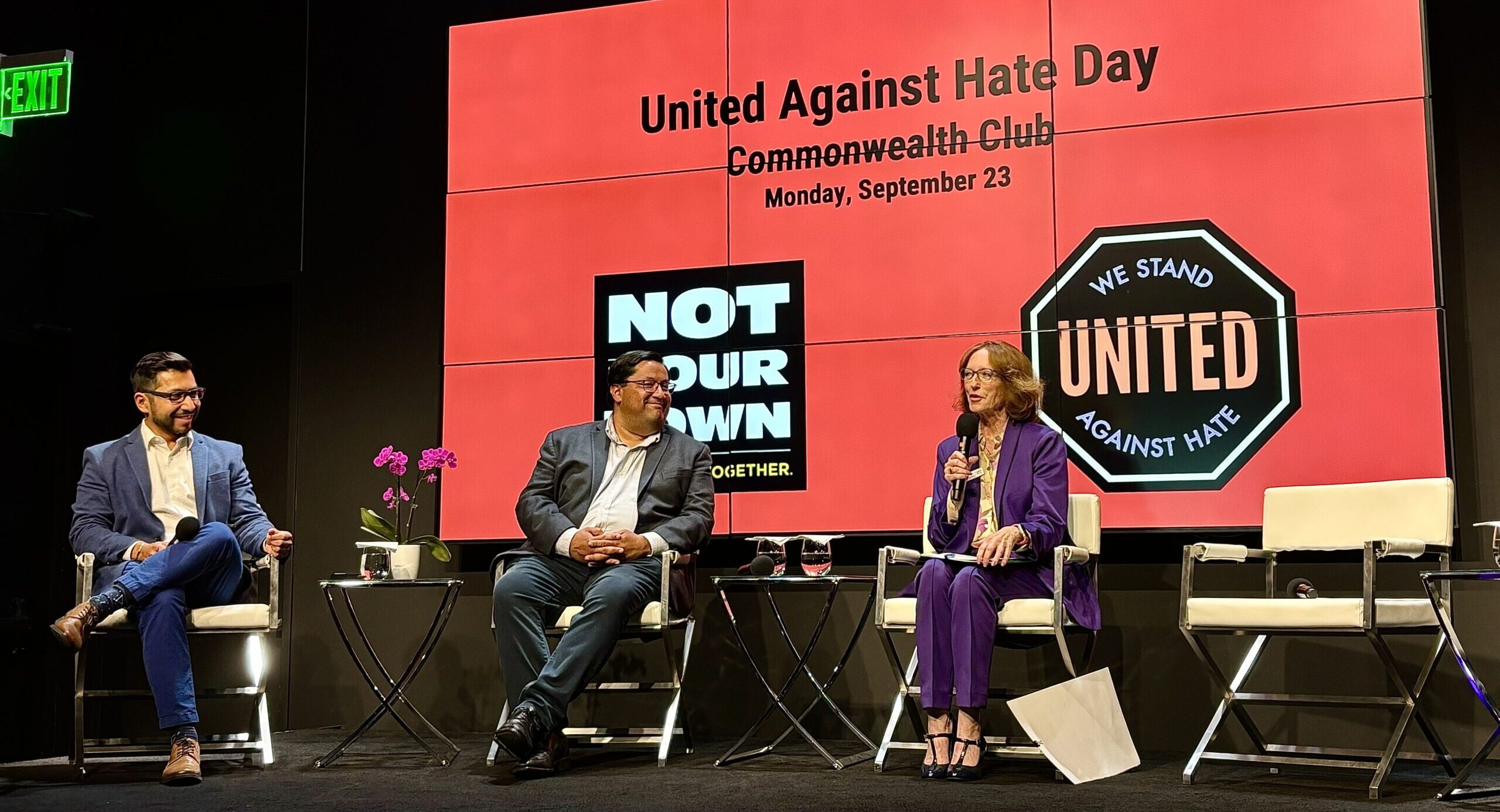

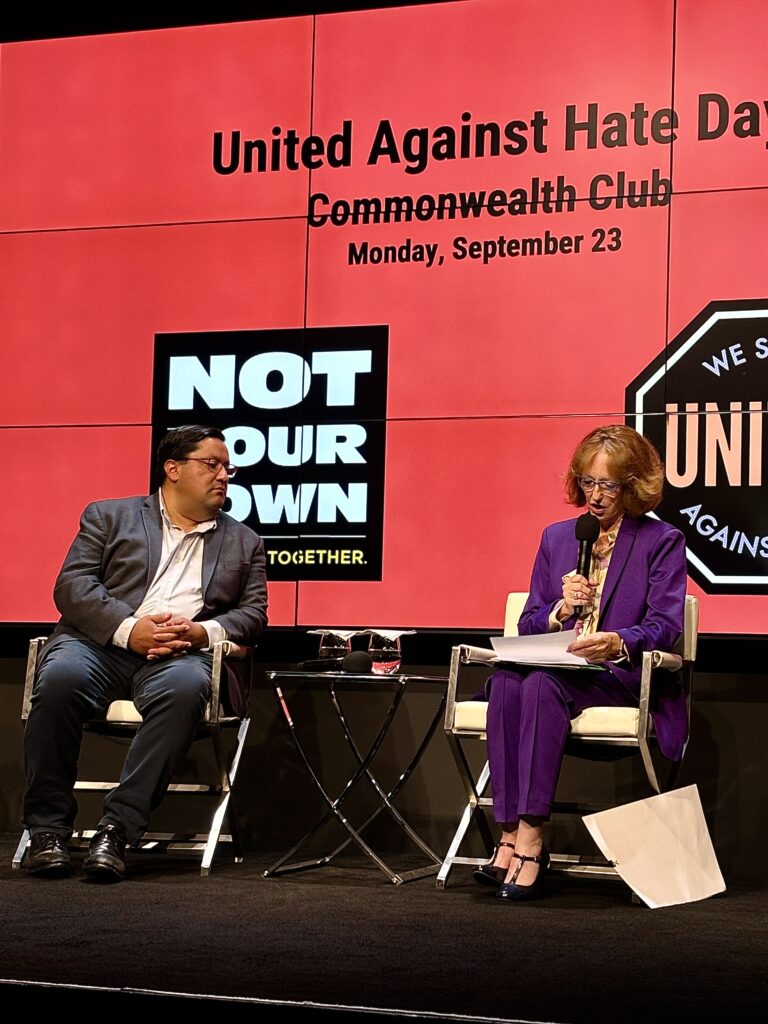

However, these initiatives often remain grassroots owing to the challenge of prosecuting hate incidents as crimes, if they are reported at all, said Anthony Rodriguez, senior advisor for Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguín at a Monday, September 23 summit at San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club commemorating United Against Hate Week.

He suggested that many groups spreading hate nationwide first tested their tactics in the Bay Area, with deadly consequences.

“We’ve seen mass killings of 11 people in Pittsburgh, 10 in Buffalo, nine in Charleston, 23 Latinos in El Paso, seven at a Sikh temple in Wisconsin, 49 people at an LGBTQ nightclub in Orlando, and then in Colorado Springs,” added Rodriguez, a United Against Hate organizer, at a panel opening the summit. “These horrific mass shootings that make the news are part of hate that happens daily.”

‘They used Berkeley as a training ground’

“I was elected mayor of Berkeley the same night that Donald Trump was elected president. It was a bittersweet evening, because I immediately saw the impact in my community, and it’s only gotten worse since then,” said Arreguín.

“Little did I expect that one of the first challenges that I would encounter as Mayor was the presence of the Proud Boys using our city as a platform for violent provocation,” he added.

The four protests, held through April, began on February 1 when British political commentator and Trump supporter Milo Yiannopolous was scheduled to speak at UC Berkeley.

In response, over 100 faculty signed a petition urging the university to cancel the event and over 1,500 protestors gathered on campus. Participants started fires, set off fireworks, threw rocks at police and attacked property and each other, with an estimated $100,000 in damages.

The increasingly violent protests culminated with a pro-Trump rally on April 15, when 500 to 1,000 people for and against the rally broke into physical assaults including smoke bombs, pepper sprays, rock-throwing and stabbing.

11 people were injured, with six hospitalized. 20 people were arrested, including far-right activists who held antisemitic signs and made Nazi salutes for groups like the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, Rise Above Movement and Identity Evropa.

“I was scared and very angry that this was happening in my city,” said Arreguín. “We later learned that these far-right groups who would later be protesting in Charlottesville, Seattle, Portland and other cities throughout the U.S. were literally using Berkeley as a training ground for their tactics … our efforts to fight it have grown over seven years into a nationwide campaign.”

The challenge of prosecuting hate

According to FBI data, hate crimes in California nearly doubled from 1,015 in 2019 to 1,970 in 2023.

Meanwhile, federal estimates suggest that as little as one in 31, or roughly 3%, of hate crimes are reported at all.

Explaining why it’s so difficult to prosecute hate crimes, Marin County District Attorney Lori Frugoli said “The issue is we have to prove someone’s mental state, that they’re committing a crime against someone because of their real or perceived race, color, religion or sexual orientation. If someone were to punch someone, for instance, it would be a simple battery, as opposed to someone battering someone while calling them a racist name. And people are learning how to walk that line.”

In the Marin town of Fairfax, Frugoli’s inability to legally file criminal charges against a man who walked that line resulted in a nationwide uproar and the passage of new hate crime legislation.

In November 2020, a young man was walking through downtown, posting stickers featuring a swastika and the words “We are everywhere.” Another young man who identified as half-Jewish followed and videotaped the perpetrator while removing the stickers and questioning him about the harmfulness of his actions and the existence of the Holocaust, which the perpetrator denied.

In the video, posted to Instagram, “The man kept saying ‘I believe in the ideology,’” said Frugoli. “The community was in an uproar overnight, and a petition with 1,000 people nationwide asked me to prosecute the charges. We have a very small county of 215,000 people, and I had only been in an office since 2019, so we really weren’t equipped to handle this properly.”

Because the stickers didn’t cause permanent damage, the incident was not vandalism, and because state law only prevented swastikas from being posted on private property, no criminal charges were filed.

“We addressed not finding the charges by saying there was insufficient evidence, a term that we use probably 20 times a week,” she continued. “We had a forum over two hours long with the FBI and local leaders, and 200 to 300 people, and people were hurt. One participant, Seth Brysk from the ADL, said ‘Do you know how painful that is, when you’re a person of Jewish faith with carrying generations of pain, to hear prosecutors talk like it’s just business?’”

“I thank him to this day,” Frugoli added. “I do now change the way that I talk about these things, putting more emphasis into why we can’t file a case, or why we chose certain charges versus others.”

In response to the forum, a group called Name, Oppose and Abolish Hate (NOAH) formed to meet with local legislators, advocate for and pass AB 2282, a 2022 bill making it a felony to use recognized religious hate symbols like swastikas, nooses and burning crosses with the intent to terrorize someone.

“When people say something vague like ‘I believe in the ideology,’ it’s often an intentional way not to be held accountable … We’re trying to find the line where we don’t violate free speech, yet hold people accountable for behavior that’s clearly intended to frighten and intimidate,” said Frugoli.

“People can walk into my office and see what we stand for, but you have to go beyond that, get out to listen to peoples’ pains and come up with a positive answer,” she added.

This resource is supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.