SAN FRANCISCO – Early in his campaign, then-mayoral candidate Daniel Lurie located his headquarters in the heart of San Francisco’s Chinatown. A nod to the voting power of the city’s Chinese American community, that decision likely helped win him the election.

But advocates say that even as the Chinese American vote reaches its peak in city politics, there are fewer Chinese elected officials today than at any time in a generation.

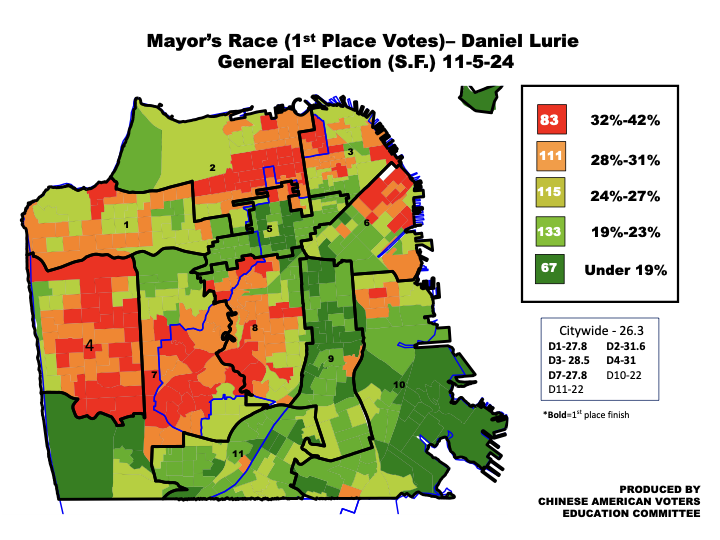

“Lurie would not have won without the Chinese vote,” says David Lee, an educator and head of the non-profit Chinese American Voters Education Committee. “Look at where his top precincts are,” notes Lee, pointing to a series of electoral maps highlighting where and how San Francisco’s Chinese Americans voted. “He placed first in District 1… in District 2, 3, 4 and 7.”

All of them except District 2 – Lurie’s home district – are heavily Chinese, Lee says.

Lurie’s opponent, incumbent Mayor London Breed, meanwhile, only won in four districts, none of which have significant Chinese populations.

“Lurie won because he was able to take away two very important pieces of Breed’s coalition,” explains Lee, “white moderates and Chinese voters. That is the difference.”

Lee says spending on political ads targeting the Chinese community marked one of the highest expenditures during the November race, some $1 million in total.

He spoke during a recent press briefing held in the offices of the Chinese Six Companies in the heart of Chinatown, an historic site where the walls themselves exude the long history of the Chinese community’s fight for representation in San Francisco dating back to the mid-1800s. A large image of the early 20th Century Chinese revolutionary leader, Sun Yat Sen hangs above.

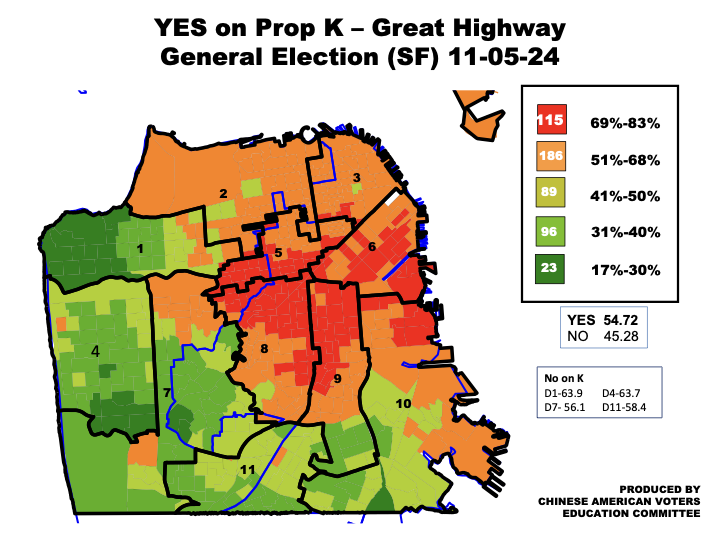

If you want to see where Chinese – about 20% of the overall population – live in San Francisco today, says Lee, just look at which districts voted “no” on Measure K, the ballot initiative that proposed to shut down a stretch of coastal roadway connecting the city’s two westernmost – and heavily Chinese – districts, the Sunset and the Richmond.

A series of green “no” votes punctuate swaths of the city, from the Richmond and Sunset in the west to the working-class Excelsior neighborhood in the city’s south and, in the center of a large red patch of yes voters clustered to the east, a small green dot: Chinatown.

The initiative, which ultimately passed, won despite near universal opposition from Chinese American voters, who argued the road’s closure would wreak havoc on neighborhood streets and close off a vital artery connecting residents to nearby family, shopping centers and other important destinations.

“I am very, very concerned about climate change. Having said that, I voted no on K,” says Henry Derr, a veteran organizer and former executive director of the progressive group, Chinese for Affirmative Action. Calling the measure “very ill-advised,” Derr says K offered no plans on how it would fund the building of a promised park, or how to manage the anticipated overflow of vehicles and its impact on surrounding neighborhoods.

But beyond that was a sense that Chinese residents – a majority in the Sunset District, adjacent to the Great Highway, where voter turnout was 81%, above the city average of 78% – had been betrayed.

“Asians are very concerned about climate issues… but the way it was done, the whole process smelled bad,” says retired San Francisco Superior Court Judge Lillian Sing, who faulted the role of billionaires in pushing personal interests over and above the interests of city residents.

“Most Chinese in San Francisco are working-class people,” she says. “They are the descendants of immigrants who really live in the city. For billionaires, San Francisco is just a property in various places. They don’t need to care about the locals at all.”

Supporters of K included the outgoing mayor, Breed, as well as newly elected District 4 Supervisor Joel Engardio, who now faces a recall effort driven by Sunset residents, 64% of whom rejected the measure. Engardio’s close links to tech-funded interest groups – which donated heavily to both Engardio’s 2022 campaign and to Prop K – are also raising questions over where his political loyalties lie.

Still, progressive Chinese candidates managed to notch a couple of important wins despite well-funded opposition.

“Billionaire funders’ number one priority was to knock off Connie Chan (in District 1) and Dean Preston,” explains Derr. Preston, who represented District 5 – which includes portions of the city’s Tenderloin neighborhood – lost his bid for re-election. “While they succeeded in the case of Preston, Chan held her seat, thanks in large part to her support from Chinese voters.”

Chan came out early against K, citing the concerns of her constituents, about half of whom are Chinese. Along with former labor organizer Chyanne Chen, who won her race for District 11, the two are the lone Chinese on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, down from three and even four in past years.

“I was the first Chinese American elected to the board of City College of San Francisco in the early 1990s,” Sing recalls. “We had three Chinese Americans on the college board at that time. This is the first time we only have one.”

That one is Alan Wong, who won despite lacking endorsements from key groups, including the Democratic Party. Instead, says Derr, Wong won on the back of a “coalition between the Chinese vote and progressive votes.”

And for the first time in recent memory there is not a single Chinese American on the San Francisco School Board. Likewise at the state level, there is no Chinese representative for San Francisco in the state capitol.

Lee, who ran and ultimately lost his bid to replace the outgoing Phil Ting for District 19 in the State Assembly, says the generation of Chinese American leaders that came of age during the civil rights battles of the 1960s and 70s – names including Ting, as well as former Mayor Ed Lee and the late influential political kingmaker, Rose Pak, among others – have retired or passed away.

“We’re rebuilding,” argues Lee, noting the success of Chinese leadership in pressuring California Governor Gavin Newsom from scrapping acupuncture from Medi-Cal coverage earlier this year.

It is, he says, an example of why representation matters, perhaps now more than ever, with San Francisco facing an imposing budget deficit that portends potentially steep cuts to vital programs and with an incoming Trump administration that has a proven track record of inciting anti-Asian and anti-Chinese hostility.

“We still face discrimination, racism,” says Sing. “America and China are fighting a trade war that will affect us. We are still seen as suspicious, as maybe traitors… these are basic issues facing the Chinese American community.”

Lee adds, “San Francisco lost thousands of residents during the Covid 19 pandemic, but the Chinese stayed. We’re still here. This is our home.”