Age isn’t everything when it comes to human health and ability, yet it often dominates conversations about these to the detriment of older adults.

In a Friday, Oct. 6 EMS briefing, aging experts discussed why ageism — discrimination on the basis of older age — prevails in the way we view older adults, and how to overcome it.

Talking about age

How we talk about aging determines much of how we experience it, said Dr. Louise Aronson, a geriatrics professor at UC San Francisco. “We were about the same age as a species for a really long time, and though now we’re a whole lot older, some things haven’t changed. Old age still ends in death.”

As far back as 10,000 B.C. until as recently as 1820 A.D., the global life expectancy was 20 to 30 years; in 2019, it was over 73.

The COVID-19 pandemic “showed us how age matters,” she added, as older adults had disproportionately greater risks and fatalities. U.S. adults 65 and over made up over 75% of COVID-related deaths as of September 2023, according to the CDC.

The health system’s very definition of older adults as anyone 65 or older, however, prevents practitioners from meeting these adults’ individual needs.

For example, “We give vaccines based on people’s biology and social behaviors, so there are 17 subcategories for children, three for adults between the ages of 19 and 64,” Aronson said. “But everybody aged 65 and up is lumped into a single category, even though a child would instantly see the physical and assume the differences between a 64 year old and 104 year old. This distinction is not based on scientific evidence about our lives.”

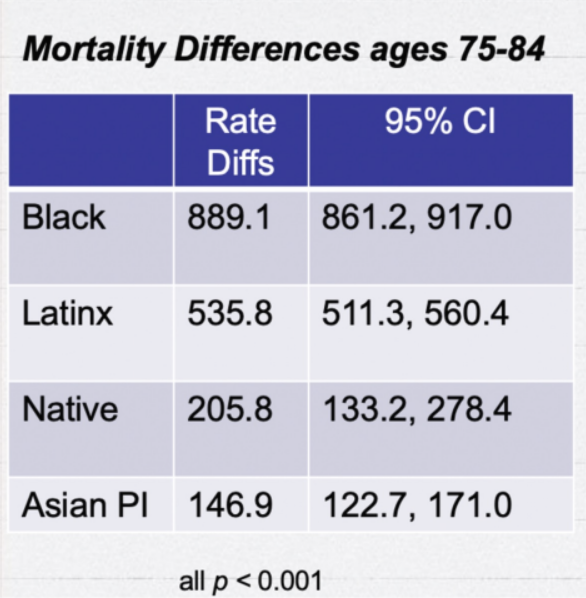

Nevertheless, “age isn’t everything,” Aronson said. Ethnic differences also compounded these risks, with Black Americans aged 75 to 84 having a nearly 900-fold difference, Latinos well over a 500-fold difference, Native Americans a 200-fold difference, and AAPI a 150-fold difference over non-Hispanic whites in the first six months of the pandemic.

This way of viewing age in terms of vulnerability to death has particular implications for ageism in the U.S., where life expectancy has declined to 76.4 years — the shortest in two decades.

However, life expectancy, too, is disproportionately divided among racial and economic lines. Even before the pandemic, for example, 56 of the 500 largest U.S. cities had life expectancy gaps up to 30 years between neighborhoods a few miles apart.

“That isn’t about biology,” said Aronson. “That’s about social choices, and where we put our money, our values and our priorities … I would like to see a world in which you may be “over the hill,” but the entire range of the hill has value … ‘anti-aging’ terminology is not helpful. The only way not to age is to die.”

The need to address ageism

Cheryl Brown, Chair of the Executive Committee for the California Commission on Aging (CCOA), said that behavioral health, caregiver training, and housing access are key to addressing ageism.

Such policies prioritizing equity for older adults are key given that by 2030, California will be home to 10.8 million older adults — comprising one-quarter of the state’s population, and nearly twice as many as in 2010.

The trend is similar nationwide: by 2030, U.S. adults 65 and over are projected to increase by nearly 18 million from 2020, comprising one in every five Americans and outnumbering children for the first time.

Brown urged efforts in other states and nationwide similar to the California Master Plan for Aging, a 10-year blueprint developed by CCOA in 2021 and aimed at supporting older adults socially, economically, and healthwise.

Ageism and Alzheimer’s

Relating ageism to Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Barry Reisberg — psychiatry professor at NYU and adjunct aging professor at McGill University — said the point at which older adults can no longer participate socially and in the workforce is later than many may think.

This point is measured clinically by the Global Deterioration Scale, which identifies the 7 stages of Alzheimer’s.

Reisberg, who developed the scale, said stage one precedes any detectable impairment of memory. In stage two, the adult “would not remember things, like names or where they place things, as well as they could five or 10 years previously”; this lasts a mean of 15 years.

In stage three, this symptom advances to “a decrease in job functioning” — e.g. organizational or travel skills — which lasts about seven years in otherwise healthy adults. Many people can go on working into this third stage and the fourth — which entails more forgetfulness of recent events — depending upon the job at hand, he emphasized.

In the fifth and sixth stages — which entail the need for help with daily activities and a greater inability to recall names — the key is to help older adults “be all that they can be as long as they can,” said Reisberg. In the seventh and final stage, which normally lasts one to two years, communication is impaired and help is needed with all daily activities, like bathing and dressing.

One way to both combat ageism and support older adults — especially in the case of health problems like Alzheimer’s — is optimizing aging through intergenerational activities” and communication, suggested Brown, wherein older adults could learn from innovations of youth and youth could learn from the experience of older adults.

Optimizing aging is not mutually exclusive but inclusive with recognizing aging, added Aronson. “Does old age come with an increased risk of illness and death? Absolutely it does,” but “age alone cannot predict which category the person is in … There are some teenagers with really good judgment, who could drive perfectly well at 14 and there are others who shouldn’t be driving at 25.”

“We need different sorts of measures than age,” she continued, “so everyone over a certain age doesn’t feel completely a part of this society … (and) won’t miss out when they could have added to it more fully.”