A young Black woman wakes up in a hospital bed and slowly realizes that she is missing most of her left arm. This is where Octavia Butler’s 1979 novel “Kindred” begins.

Published just three years after the “Roots” miniseries introduced millions to the origins of Black Americans in chattel slavery – and the lives of African people before enslavement – “Kindred” was one of the first great novels to envision that generational trauma through a contemporary character.

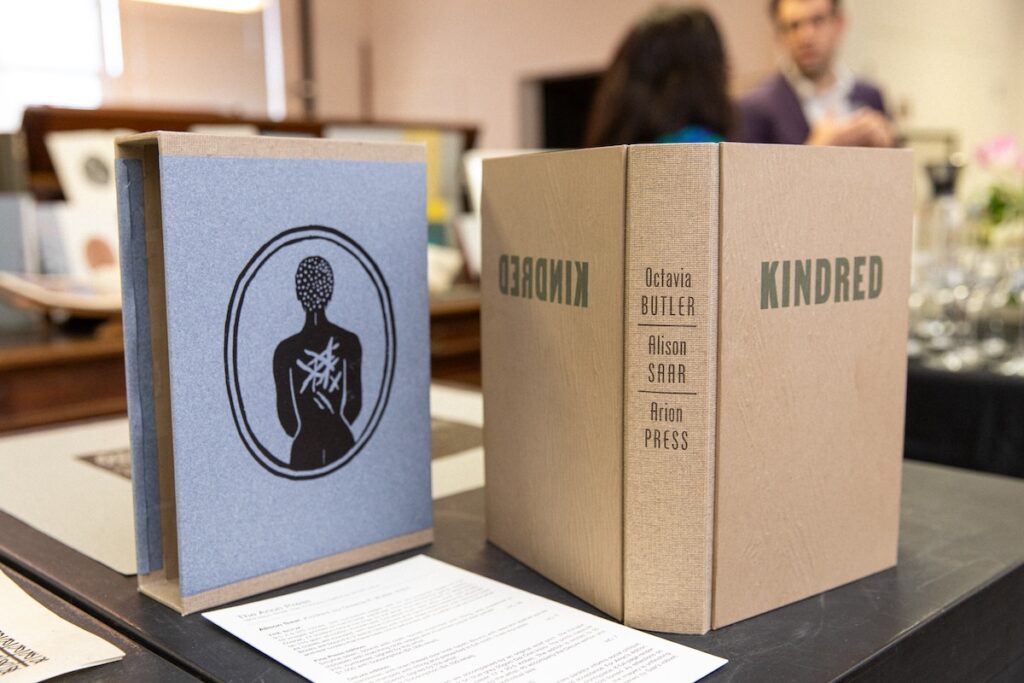

A new handmade edition of the book is being released by the San Francisco-based publisher, Arion Press, the only American publishing house where every aspect of a book “from comma to cover” is made by hand.

This latest Arion release unites Pasadena native Butler, who died in 2006, with another great Black California artist, Los Angeles sculptor Alison Saar, whose work has long focused on the African diaspora.

“I chose ‘Kindred’ because a lot of my work talks about the present political situation through the eyes of African American history,” said Saar. Artists who accept Arion’s invitation get to choose their book project.

Her remarks are in part a reference to the recent wave of book bans and the “active erasure” of history seen in classrooms across the country. PEN America identified 3,362 individual instances of books being banned – including “Kindred” by the Wentzville, Missouri school district – in the 2022-23 school year. The bans impacted 1,557 titles across 33 states, with most (40%) occurring in Florida.

For Saar, “Kindred’s” treatment of slavery and African American experiences offers a powerful rebuke of attempts to “rewrite the history.” “Kindred” is set in 1976, America’s bicentennial year.

Dana, the novel’s heroine, is unpacking in her new California home when she gets sucked back to 1815 to save Rufus, a young white boy who is drowning on a Maryland slave plantation. She is only able to return to her own time and place when her life is in danger.

As this cycle of rescue and escape repeats over the next several days (in present time) and the next several years (in past time), Dana learns that Rufus is one of her ancestors. In order for Dana’s family to exist in the 20th century, she has to make sure that Rufus lives long enough to rape one of her foremothers in the 19th century.

“I thought it was really important to focus on this piece that talked about this history in really graphic terms and [Dana’s] experience and understanding and the complexities of her having to save her enslaver, her family’s enslaver,” Saar said.“Kindred” is the first of two limited runs of literary classics that Arion will publish during its 50th anniversary year. (Ordinarily Arion produces three projects a year, but this fall they are moving from their home in the Presidio to a new space in San Francisco’s Fort Mason Center.)

In addition to 40 deluxe editions, which come with a Saar print, the seven full-time Arion craftspeople are making 210 “fine print editions.” Subscribers pay $2,400 for a year’s run, while individual editions cost $1,300.

Ted Gioia, Arion’s development director, says the first copies are now ready but given the scores of hours needed to make each book the rest will be released over the summer.

Arion collaborates with fine artists, such as Saar, painter Kara Walker and sculptor Martin Puryear – whose gallery and museum works are valued at 20 to 1,500 times what an Arion book costs – to produce readable works of art.

Saar, who this week will be directing the installation of one of her bronze works in the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park in Montgomery, Alabama, said she first became aware of Arion because her mother, the celebrated artist Betye Saar, owned the edition of Jean Toomer’s novel “Cane,” that Arion made with Puryear. “Having seen that publication – I mean, they are little sculptures, they’re just incredible.”

The level of design, detail and fine handiwork that goes into making Arion’s books is reminiscent of couture dressmaking, where the inside is as beautifully made as the outside.

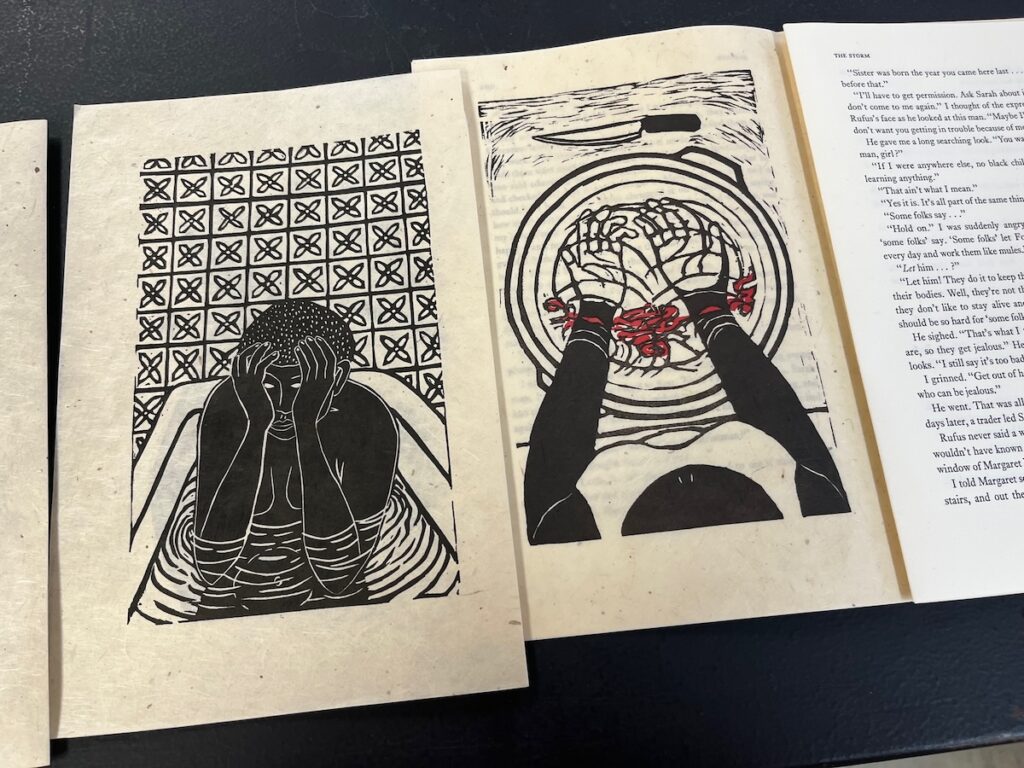

Saar carved linoleum block illustrations for the chapters, the end papers and a single red page at the book’s beginning to represent the Yoruba orisha, or spirit, Elegua. Although Elegua is not a character in the novel, the addition of the page is the artist’s homage to Butler.

“I’m very much involved in deities and lwas (loas) from the African diaspora and this is Elegua, the guardian of the crossroads,” Saar said. “I love that [Dana] goes between two worlds and that’s [Elegua’s] role as a messenger to bring…information from the spirit world to our world here…. Her making these journeys between these two worlds kind of fit in with that as a protector of the past and her ancestors.”The title “Kindred” on the cover is in the “Martin” (for MLK) font, by Black typography designer Tre Seals, who based it on the posters carried in the 1968 “I Am a Man” sanitation workers’ protest.

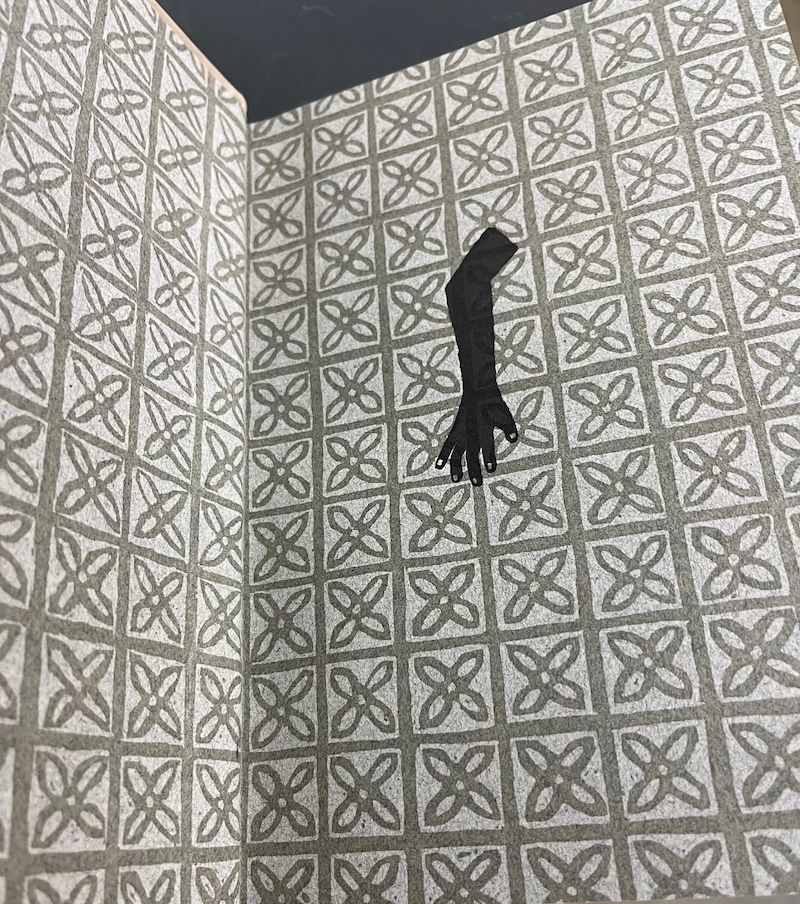

The book’s front end paper – the decorated paper lining a book’s cover – features Saar’s image of Dana’s severed arm protruding through a wall seen as a background detail in one of the illustrations. The rest of her body is on the book’s closing end paper.

The heft of this edition of “Kindred” was intentional. “The thickness…the presence of the book, kind of talks about this passage of time, this experience as we’re slowly led along this history, the limbo between these two worlds,” said Saar, “and I like that we were able to physically express that.”

While many of the books will be purchased by what Gioia calls “white glove collectors” who will treat them like archival treasures, others will go to people who will read them and delight in how they feel in their naked hands. Visitors to an Arion breakfast with Saar were encouraged to touch the raised type and to press their hands against the bark textured leather cover meant to evoke a tree Dana might have hidden behind.

Saar said she had seen where Butler had written “make them feel” in one of her notebooks. Seeing Butler’s drafts fascinated and inspired her.

“She’s constantly writing and rewriting in the margins. As a sculptor I love this word ‘honing.’ You go in and continually refine these surfaces or edges. I feel a real kindred with her,” she giggled, “in that we have this real interest in the refinement. But not such a refinement that it becomes artificial. It’s still visceral and intense and has immediacy to it. To get to that through reworking and choosing the right word, it’s really amazing to me.”

Although contemporary readers are excited by the Afrofuturistic aspects of Butler’s later works, Parable of the Sower among them, Saar feels this is the time for “Kindred.”

“Slavery is often a way that I speak of what we are experiencing here and now,” she said. “I felt that this book was doing a similar thing, talking about contemporary issues by going back and seeing this dark history and how we’re still experiencing the aftermath of that.”

Teresa Moore is a freelance writer based in San Francisco.